It is said that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. In today’s society, the urge to protect seems to be omnipresent. Perhaps this was best reflected at the start of the pandemic when Prime Minister Boris Johnson promised that the country would be ‘putting our arms around every worker’. It seems that the pandemic was the time that the urge to protect took a vice-like hold of the country – but this has been a process that has been a long time in the making and one that has shifted perspective. Today it seems it is hard to do anything without some attempt to protect us from our worse self: food labels outlining what we should and shouldn’t eat; calorie totals on restaurant menus; sugar taxes to guide us away from the dreaded white death; trigger warnings on even the most innocuous TV shows; help lines after these shows just in case we have been affected by something; and re-writing books in case there is a phrase that upsets us. With all this danger lurking around every corner, it seems amazing that we coped in the dangerous world of the past and before these kind people decided to protect us from our worst excesses.

However, some might say we coped pretty well and perhaps this ability to cope with stressors is something we need to revisit. A feature of many of the protectional strategies is the attempt to protect through limiting our exposure to what is deemed potentially harmful. By wrapping us in a cocoon, the hope seems to be that we will not be subjected to any stresses or worries that may take us away from our comfort zone. Yet how well is this working? In many cases not that well – in numerous instances many of the issues we are meant to be protected from are in fact on the rise. Could it be that this approach to protection reduces our ability to cope, actually making things worse rather than better? Indeed, some fields are now suggesting that we may have entered an era of over-diagnosis and over-protection.

It is always important to remember that, while the instinct to protect is inherent, it needs to be balanced with an understanding of the bigger picture. The protective nature, if left unchecked, could lead to a vicious circle, where lack of exposure leads to a lack of capacity to cope, leading in turn to a need for lesser exposure ad infinitum – a true vicious circle. As psychologist Jonathan Haidt suggests: ‘the problem with an “everything is dangerous” outlook is that over-protectiveness can rapidly become a danger in and of itself’.

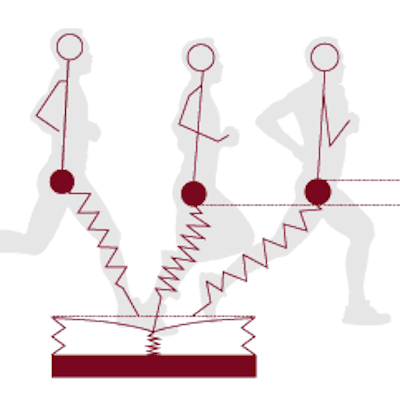

Crucially there is another approach, one more associated with the German philosopher Nietzsche – in German 'Was mich nicht umbringt, macht mich stärker', but we are more familiar with the English ‘what does not kill me makes me stronger’. In other words, although we can protect through limiting exposure, we can also protect by progressively increasing exposure, by building the capacity to tolerate stressors and thus enabling us to cope with ever challenging situations. In strength and conditioning, we build tolerance to stressors through developing our fitness capacities, and – as we all know – this requires progressive challenge. Although this might be obvious, if we step back is this always the direction of travel we are taking or are we too falling into the trap of over-protection?

Today, concepts such as load monitoring, screening, imbalance assessment etc. are ubiquitous. Now there is nothing necessarily wrong with these approaches, and indeed they have many potential benefits, but they also shape our perspective especially when viewed through a protection-based lens. In so many fields, the scourge of over-diagnosis is prevalent, and this is causing issues; in the words of Steve Jobs: ‘there are downsides to everything, there are unintended consequences to everything’. If the focus of our monitoring and diagnosis is to control, to limit exposure, to simply correct do we run the risk of over protecting and developing fragility? On the other hand, if our approach is to challenge, to progress, with a focus on building the capacity to cope with even greater stressors, do we build what Taleb calls a more ‘antifragile’ individual?

As in so many fields, the answer lies in balance and here it is necessary to accept the reality of both elements. Those with a protective tendency must become comfortable that performance requires the pushing of boundaries and that over-protection can limit the potential for growth, limit performance and actually increase the likelihood of injuries. Equally, the more challenging types, prone to always pushing the envelope, must be comfortable that there will be times where this cannot be done and where ever more load could result in breakdown and thus a more conservative approach could be considered. What is important is that we understand there is no fixed answer; however, we do need to be aware of where our dial is, reflect upon the best approach needed in any given situation, and learn how to re-steer our course if we are drifting too far in any one direction.

1. Allison, M and Allison, E. Managing Up, Managing Down. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. 1986.

2. Batra P. Eisenhower box for prioritising waiting list of orthodontic patients. Oral Health and Dental Management, 16: 1-3. 2021.

3. Covey S. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. New York, NY: Free Press. 1989.

4. Duhigg C. The Power of Habit. New York, NY: Random House Publishing Group. 2013.

5. Duhigg C. Supercommunicators: How to Unlock the Secret Language of Connection. New York, NY: Random House Publishing Group. 2024.

Ian is a prolific coach, author and educator who consults extensively with several international sports organisations. He is President of the NSCA, Editor of the UKSCA's journal, Professional Strength and Conditioning, and is also on the Editorial Board for the NSCA's Strength and Conditioning Journal, and the Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning.