Dr Iain M Fletcher, principle lecturer, University of Bedfordshire, Bedford, and Dr Sean Maloney, Maloney Performance

High levels of vertical, leg and joint stiffness are generally advantageous for short time span performance actions, with stiffness changes sensitive to training. Consequently it is vital to monitor stiffness changes in any training intervention designed to enhance stiffness. Measures of stiffness are often seen as too complex to be carried out as part of a training intervention, but this approach misses key adaptations which drive performance.

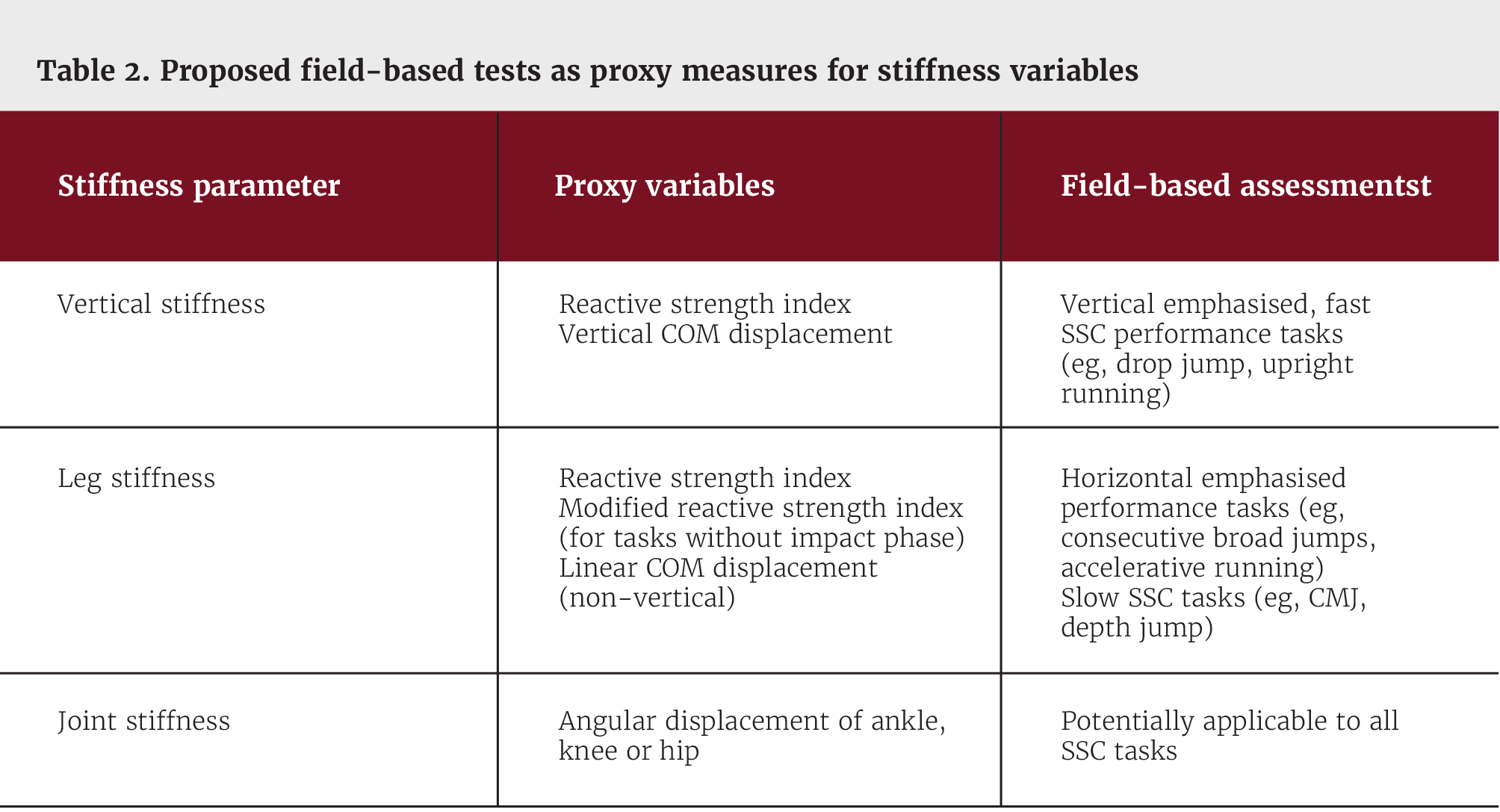

Part 2 of this narrative review focuses on measurement methods that are accessable to coaches and how subsets of stiffness can be trained. To measure a structure’s stiffness, there is a requirement for the force applied to and the corresponding change in length of a given structure (Hooke’s law). Vertical stiffness focuses on centre of mass (COM) displacement, rather than compression of the leg-spring seen in leg stiffness measurements. This makes leg stiffness a preferable measure, compared to vertical stiffness, if more horizontal movements are explored. However, leg stiffness will miss torso deviations in vertical actions and should not be used to replace COM deviation seen in vertical stiffness measures.

Joint stiffness measures individual joint actions, giving valuable insight into how joints impact system stiffness. Measures of stiffness require high technical knowledge and complex equipment, often beyond the scope of coaches. However, practical monitoring of stiffness can be relatively easily accomplished by tracking temporal and performance outcomes interactions reliably via readily available high sampling frequency phone apps. Enhancing stiffness has been achieved with isometric, eccentric, isotonic and plyometric training, frequently linked to higher intensity interventions, whether acute or chronic stiffness increases are required. Interventions must maximise force output without increasing ground contact or contraction time, while it is recommended to sequence structural, neural and coordinative-based objectives in any training intervention.

Part 1 of this narrative review explored the concept of stiffness in human movement, highlighting the use of different spring models to look at ground impacts, the distinctions between vertical, leg and joint stiffness, and how each influences human performance. A key takeaway was that increases in stiffness are generally associated with performance across a range of performance tasks, but that vertical, leg and joint stiffness, though inter-related, are distinct constructs which should not be used interchangably as they have different performance impacts that must be trained and assessed independently to fully optimise performance.

The role of stiffness in enhancing performance lies in the body’s ability to absorb impact forces, store energy, and increase concentric force output once impact force is removed and structures return to resting length.20 Therefore, elastic tissue will absorb and store energy as it deforms during a ground impact event; the active component of the muscular tendinous unit (MTU) will have to produce an impulse at least equal to the body’s momentum during an impact event to stop motion enabling the release of stored elastic energy to help enhance the propulsive phase of a given movement. High levels of stiffness – whether vertical, leg or joint – are generally advantageous for executing performance actions efficiently in a short time span.51 Consequently, if stiffness impacts performance, it becomes essential to monitor it in order to see meaningful changes over time.

Before discussing measurement methods, it needs to be established that it is a modifiable variable that is sensitive to training. Nagahara & Zushi48 explored the vertical and leg stiffness in trained male sprinters (average 100 m time 11.22 s) over a 6-month training block. They found a 56.4% increase in vertical stiffness alongside a 5.7% increase in maximum sprint velocity. Interestingly, no change in leg stiffness was reported. This could be attributable to task specificity, as Part 1 of this review indicated that vertical stiffness is more closely linked to max velocity running, with leg stiffness more closely linked to slower stretch shortening cycle (SSC) actions.

Given the importance of stiffness in human performance and its observable trainability, it is vital that stiffness is measured in a meaningful way to establish the efficacy of the training programme and manage injury risk.9 However, stiffness remains an underutilised and misused metric among S&C coaches. Practitioners and researchers have frequently used measures of stiffness (particularly vertical, leg and joint) interchangeably and incorrectly, which is problematic as Part 1 of this review indicates these separate aspects of stiffness impact performance differently. Coaches may perceive the complexity of measuring the various components of stiffness across the human system as impractical or too time-consuming to be of practical use. However, the links stiffness has to performance and injury mitigation means that the benefits from understanding and being able to monitor stiffness changes outweigh any perceived issues with measurement. For instance, an intervention designed to increase running velocity, that does not look at changes in vertical and ankle stiffness, is missing key structural adaptations which influence how fast humans run. Therefore, this review will concentrate on more global measures, such as vertical and leg stiffness, as they help explain whole body movement performance. Additionally, the inclusion of joint stiffness measures may serve to highlight potential ‘weak links’ in these global measures and will be included in this review.

Part 2 of this narrative review focuses on practical applications to strength and conditioning (S&C) coaches. First, methods for measuring and monitoring stiffness will be considered in a way that is both accessible and meaningful for coaches in applied settings. Second, we shift focus to the practical application of stiffness training, examining how the different subsets of stiffness can be developed to enhance human performance.

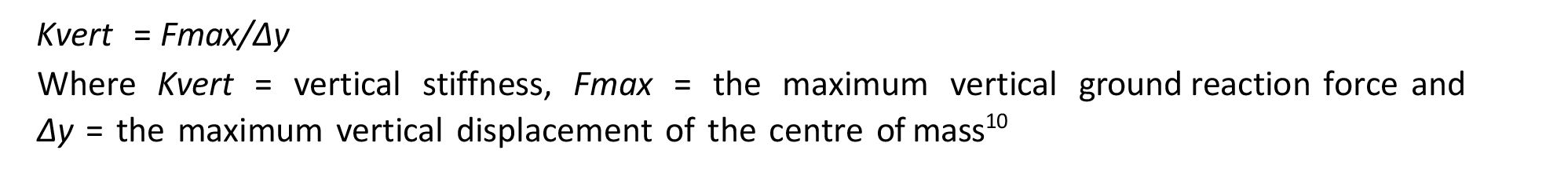

Vertical stiffness can be calculated by the following equation:

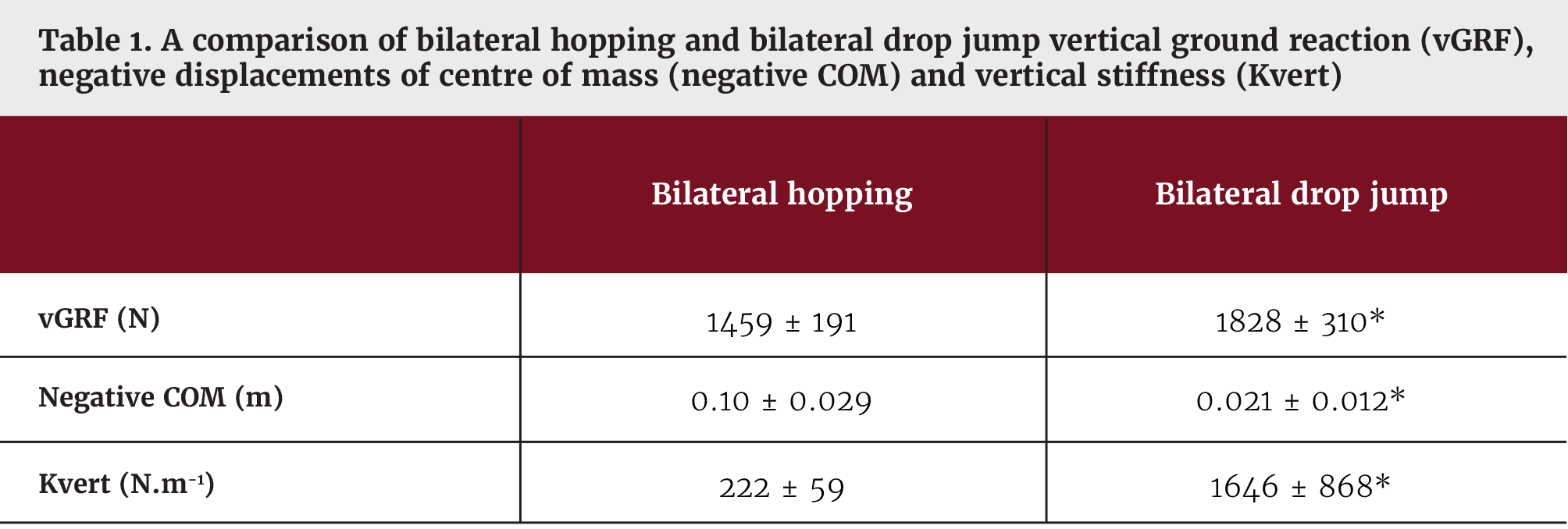

Vertical stiffness in research is frequently calculated via sub maximal bilateral repeated jumps (equivocally referred to as ‘hopping’) at set frequencies.22,21,51 However, this method considers only sagittal plane movement and may not represent the maximum intensity actions seen in sporting performance. ‘Maximal’ vertical stiffness has been measured bilaterally using drop jump actions3,38 and maximal repeated hopping.7 These high-intensity actions may better reflect the demands of high-speed sports, given the greater forces and centre of mass (COM) displacements involved. Notably, these maximal tests yield substantially different vertical stiffness values compared to submaximal hopping, highlighting the influence of intensity on stiffness measurements. Table 1 shows that increased vertical force and a decrease in COM displacement in drop jumping compared to hopping, with a noteworthy nearly eight-fold increase in vertical stiffness when these tasks are compared.36

NB. Figures are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *indicates significantly difference to bilateral hopping (P <0.01) (adapted from Maloney et al36)

Despite their relevance to high-speed actions, bilateral measures may not fully replicate the cyclical, unilateral nature of movements like running. To address this, Maloney et al38 also explored unilateral drop jumping, finding similar vertical stiffness values to bilateral assessments when performed from the same drop height. While unilateral drop jumping generates higher ground reaction forces (GRFs), the increased COM displacement appears to compensate, maintaining comparable stiffness outcomes. Vertical stiffness has also been measured more directly in high-speed treadmill running and over ground running,43,48 making these measures more applicable to sagittal plane sporting actions. However, these methods require a force plate or an instrumented treadmill. The high cost, time demands, and technical expertise needed make such measures impractical for most S&C coaches.

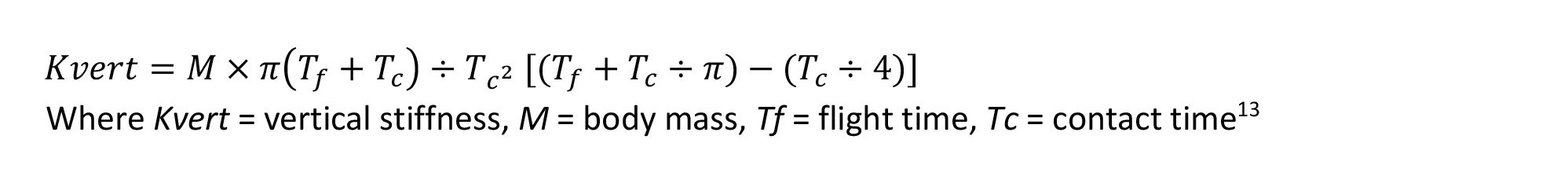

Due to the inaccessibility of force measurement devices for many, field-based estimations of vertical stiffness have been suggested. For example, Dalleau et al13 developed validated estimations using body mass, flight time and ground contact time (Equation 2). These estimations demonstrated a strong correlation with vertical stiffness values obtained from force plate measurements for bilateral hopping between 1.8 and 4 Hz (r = 0.94 to 0.98). Extending this principle, Morin et al46 validated the use of the sine wave method to estimate vertical stiffness during running (r2 = 0.97 to 0.98 versus direct measurements). These advancements show that vertical stiffness can be reliably determined using temporal data (eg, flight and contact times). This allows S&C coaches to assess stiffness with accessible tools such as switch mats, photocell systems, and even smartphone applications.

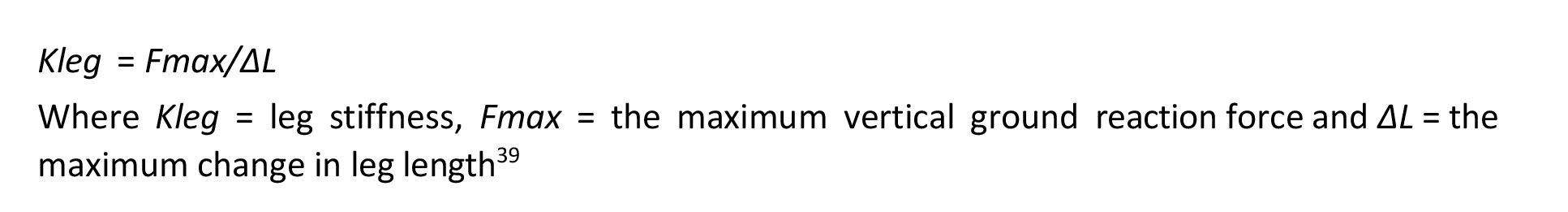

Leg stiffness can be calculated via the following equation:

Where Kleg = leg stiffness, Fmax = the maximum vertical ground reaction force and ΔL = the maximum change in leg length39

Measurements of leg stiffness seek to determine compression of the leg-spring, as opposed to vertical stiffness assessing displacement of the COM.39 Thus, leg stiffness may be a preferred measurement when actions emphasise horizontal or lateral movement, such as acceleration or COD.10 However, it is more complex to calculate than vertical stiffness as it typically requires measurements of resting leg length, ground contact time, horizontal velocity, vertical GRF and COM displacement.39 Nonetheless, as with vertical stiffness, Morin et al43 validated the use of field-based estimations using anthropometric and temporal data (r2 = 0.89) versus direct measurements during over ground running. Morin et al43 calculated that their model underestimated leg stiffness by 2.54 ±1.16% compared to a gold standard force plate method. This should be born in mind by any practitioner wishing to use this estimation, but seems a reasonable trade-off for a field-based test.

When an action is measured with the COM moving exclusively in the vertical plane, vertical and leg stiffness may be identical.10,39 This has led to some researchers using these terms interchangeably. However, doing so is probably misleading, particularly during maximal tasks. For instance, if maximal sprinting or drop jumps are used to analyse stiffness, leg stiffness and vertical stiffness will differ. At these higher intensities, the torso will deviate during ground contact to mitigate high GRF, a factor leg stiffness does not consider. This distinction is crucial for coaches to understand, as the choice between measuring vertical or leg stiffness should align with the specific demands of the activity being assessed or trained, ensuring that the most relevant parameter informs programme design and athlete monitoring. For example, a coach interested in only leg stiffness during maximal velocity running may miss the torso ‘collapsing’ during ground contact negatively effecting performance.

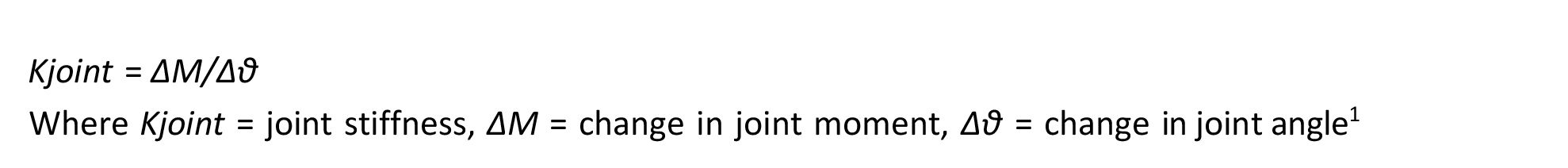

Joint stiffness can be calculated via the following equation:

Both vertical and leg stiffness approximate the compression of a single mass, which encompasses contributions from the ankle, knee, and hip. Measuring joint-specific contributions can provide valuable insights into how each joint impacts overall system stiffness, offering practical applications for coaches in tailoring training or addressing performance limitations. To measure joint stiffness, net joint moments and joint angular displacement are required. For simple uniplanar movements, recording angular displacement, with several smartphone applications capable of sampling at 240 Hz, considered an adequate frequency for capturing gross human movement which does not involve interaction with equipment.29 However, when assessing multiplanar movements, more advanced tools such as 3D motion analysis systems are necessary. Moreover, estimating net joint moments adds complexity, often requiring specialised equipment and a high level of technical expertise.

Coaches should be aware that stiffness is not a performance variable. The measurement of stiffness confers the S&C coach with information as to how an athlete achieves a performance outcome. As such, the stiffness value observed in a task must be considered alongside the outcome variable (eg, jump height or sprint time). Coaches must also consider that the stiffness value obtained in a given task is not meaningful in isolation. For example, a stiffness value of 1646 N.m-1 from a bilateral drop jump provides little actionable insight for a coach. Stiffness may provide useful insight, and subsequent performance applications, when considered in the light of normative group data (ie, within a team or training squad) or normative individual data (ie, longitudinal changes).

Understanding the kinetic basis of human movement can highlight variables to monitor for stiffness changes where field settings preclude the direct measurement of force. Movement is driven by a series of accelerations, or changes in velocity, involving the limbs, centre of mass (COM), or external loads. According to Newton’s second law, impulse (∆force × ∆time) causes these accelerations. Winter et al56 explains: ‘Maximal neuromuscular efforts aim to maximise impulse, as it determines resulting velocity.’ In sporting contexts, efficient and rapid force production is critical. As Taube et al53 note, faster impulse generation in stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) activities often determines success. Ground-based actions like running and jumping rely on minimising ground contact time, while producing sufficient force to achieve high velocities. Stiffness plays a key role here, as efficient elastic stretch and recoil allow for high force output within short time spans.

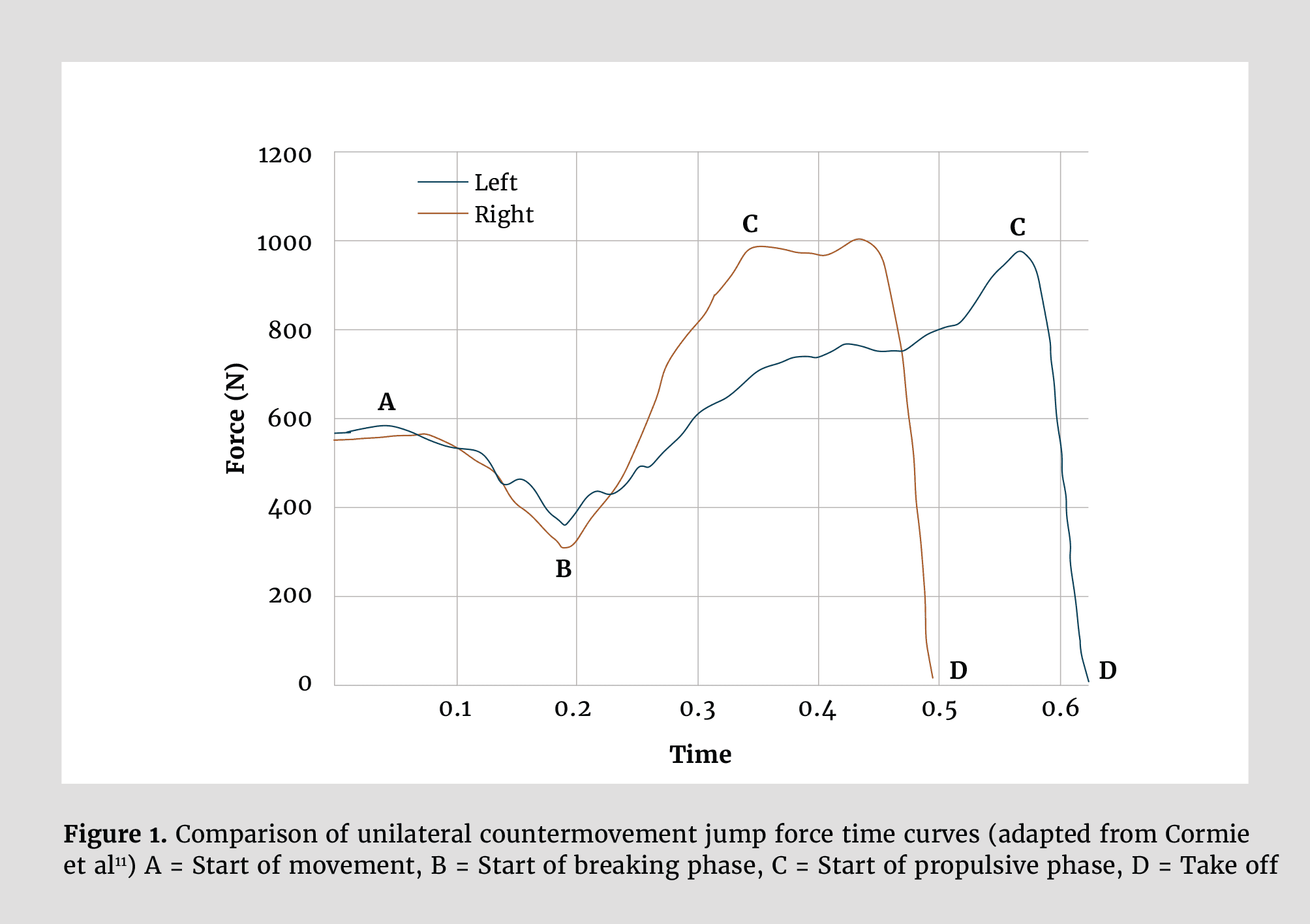

To monitor stiffness changes practically, tracking temporal and performance outcomes is more accessible than measuring force or stiffness directly. For instance, in drop jumps or countermovement jumps (CMJ), if an athlete’s mass remains constant, but their jump height increases, they must have produced more impulse. For stiffness to contribute, this greater impulse must occur within the same or a shorter ground contact time. By observing jump height or distance relative to ground contact or contraction time, coaches can infer global changes in stiffness. This approach offers a practical and meaningful way to monitor stiffness adaptations in an applied setting. Figure 1 is a practical example of this approach, comparing the force time curves for a left and right leg countermovement jump. The two jump heights are very similar (0.1 m left vs 0.12 m right), with the left leg jump producing a peak force of 977 N, and the right leg producing a very similar force of 1005 N. Superficially, this may suggest the jump performance is quite similar, but the application of force varies greatly. The left leg jump applies force for far longer than the right leg in order to generate the impulse necessary to cause the countermovement jump. Therefore, although impulse is similar for both jumps (80 Ns left vs 90 Ns right, the right leg produces necessary impulse in a shorter time frame for a similar performance outcome indicating a faster transfer of force through the system, implying a stiffer, more effective, jump via the right leg.

In the proposed examples, vertical stiffness changes could be monitored via the reactive strength index (RSI) (flight time/ground contact time) in a drop jump. RSI is correlated to fast SSC performance such as COD and max velocity sprinting,58 but key to this review is that it also significantly correlates to vertical stiffness measures.37,25 This approach is suggested by other practitioners, with Brazier et al9 commenting that RSI can be used to provide feedback to the athlete/coach to enhance performance.

A working example from a drop jump:

Pre-intervention: flight time = 0.42 s, ground contact = 0.24 s

RSI = 1.75

Post-intervention: flight time = 0.42 s, ground contact = 0.18 s

RSI = 2.33

Jump height (flight time) did not improve, so impulse did not increase. However, as ground contact decreased and RSI improved, force output has increased to allow a shorter ground contact to generate the required impulse for a 0.42 s flight time. Therefore, we can assume force transmission to the ground has improved via increased stiffness.

To support this hypothesis, measuring angular displacement ankle function (the greatest joint contributor to vertical stiffness) will give greater understanding of whether key structures linked to vertical stiffness have been improved. In the proposed example, as ground contact has decreased, it is likely that the ankle will have either decreased its ROM, or decreased time to achieve the same ROM. Either way, stiffness of the ankle joint will have been increased.

The modified RSI (mRSI) measure (flight time/contraction time) has not been explored to the same extent as drop jump derived RSI, but may be a useful way to explore slow SSC actions. Measurements of stiffness can be calculated from squat and countermovement jumps.57 These tasks do not incur impact forces and do not represent how the leg-spring is typically loaded during sporting activities. However, they do examine slow SSC function, key to actions such as counter movement jumping (CMJ) and initial acceleration, by looking at the interaction of flight time and contraction time during the jump. Again, this variable may help give an understanding of changes in stiffness.

A working example from a CMJ:

Pre-intervention: flight time = 0.64 s, contraction time = 0.43 s

mRSI = 1.49

Post-intervention: flight time = 0.72 s, contraction time = 0.43 s

mRSI = 1.67

As flight time (jump height) in the CMJ has improved, therefore greater impulse has been produced. As the contraction time has not changed, force production has increased in this time span, hence an improvement in mRSI. Therefore, this increase suggests that force has been transferred more efficiently to the ground, assuming greater stiffness.

In this example, measuring angular displacement of the knee (the greatest joint contributor to leg stiffness), will give greater understanding of whether key structures linked to leg stiffness have been improved. As ground contact time has not changed, it is expected that the knee ROM and time for this deviation will not have changed. However, as the propulsive impulse has increased, the joint is anticipated to be acting more stiffly as it copes with greater forces in the same time span. This contention is supported by Knudson et al,26 who surmised that joint stiffness can be estimated from the knee movement in vertical jumps.

The use of jumps to look at fast and slow SSC function is useful to monitor changes in function, but does not consider the specific application to tasks such as sprinting and changing direction. It is more complicated to estimate stiffness during these tasks; for example, using the equation first validated by Morin et al43 discussed in Part 1. However, simple temporal data may be used to provide coaches with a suitable proxy estimation. Timing gates or smartphone applications can provide valid and reliable measurements of sprint time. Photoelectric systems and smartphone applications can then provide valid and reliable measurements of flight and ground contact times.

Pre-intervention: Flying 10-m time: 1.05 s, mean GCT: 0.12 s

Post-intervention: Flying 10-m time: 1.00 s, mean GCT: 0.12 s

Here, mean velocity of the athlete has increased whereas mean GCT has not changed. Thus, it is assumed that net impulse has increased. In the presence of no change in GCT, this is indicative of a stiffer global system. As with the previous jump examples, coaches may then examine changes in COM or joint kinematics to elucidate further information. For example, where vertical stiffness is the key factor, coaches may wish to consider the change in COM height during this task, from the instant of ground contact to mid-stance. This could be easily estimated by tracking the vertical displacement of the iliac crest as a de facto marker of the COM.

Some aspects of testing need to be born in mind when exploring performance. The type of warm-up used needs to be standardised, as this can dramatically effect results.16 The state of fatigue will have an impact on measures:44 it is recommended to test when performers are relatively recovered, eg, after a de-load week of training if testing is to be performed on a block-by-block basis. Lastly, surface and footwear will impact measures: stiffness compensates for surface changes, increasing for soft surfaces and decreasing for hard.45,47 Therefore, the same footwear and surface should be employed regardless of the type of assessment.

It must be recognised that the approach outlined in this article has an element of inherent subjectivity. This may negate its use for the determination of stiffness for peer-reviewed research purposes, at least without formal determination of reliability and validity. However, as cost-effective, portable and accessible field-based monitoring options, they may guide coaches to making more informed decisions around planning training programmes.

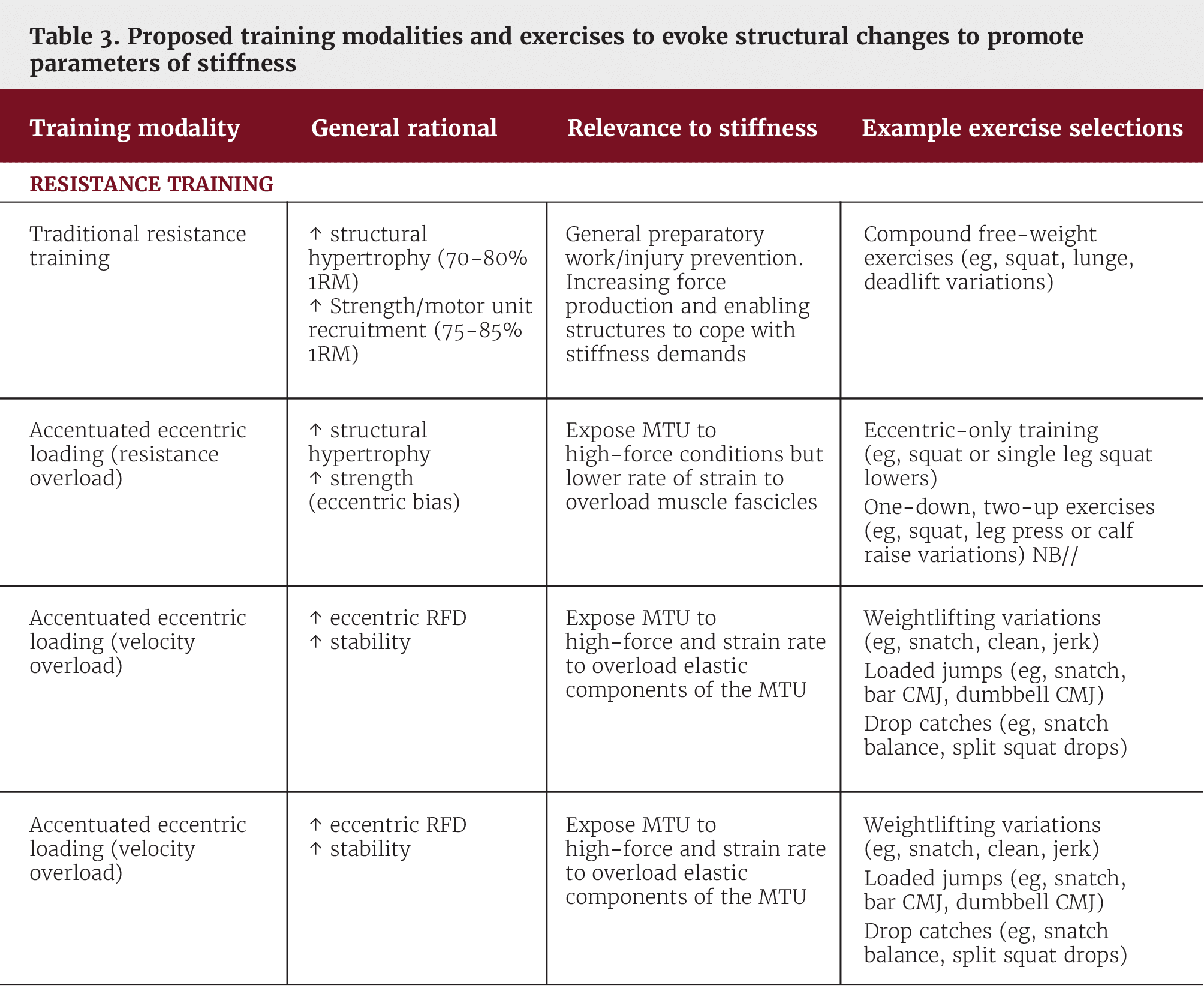

Global measures of lower limb stiffness may be enhanced in response to a range of different training interventions. Both resistance training, whether isometric, eccentric or isotonic, and plyometric training have been shown to augment stiffness.8

Chronic interventions have been shown to positively impact stiffness and performance, with evidence supporting the importance of exercise intensity. For instance, García-Pinillos et al18 demonstrated significant improvements in stiffness using a 10-week low-intensity (jump rope/skipping) plyometric programme. Kubo et al28 reported improvements in tendon stiffness and reductions in hysteresis following a 12-week unilateral plyometric programme of sledge hopping and drop jumps. Tendon adaptations correlated with enhanced jump performance, with CMJ height benefitting from both tendon mechanical improvements and altered neuromuscular strategies, while drop jump performance was more reliant on mechanical changes.

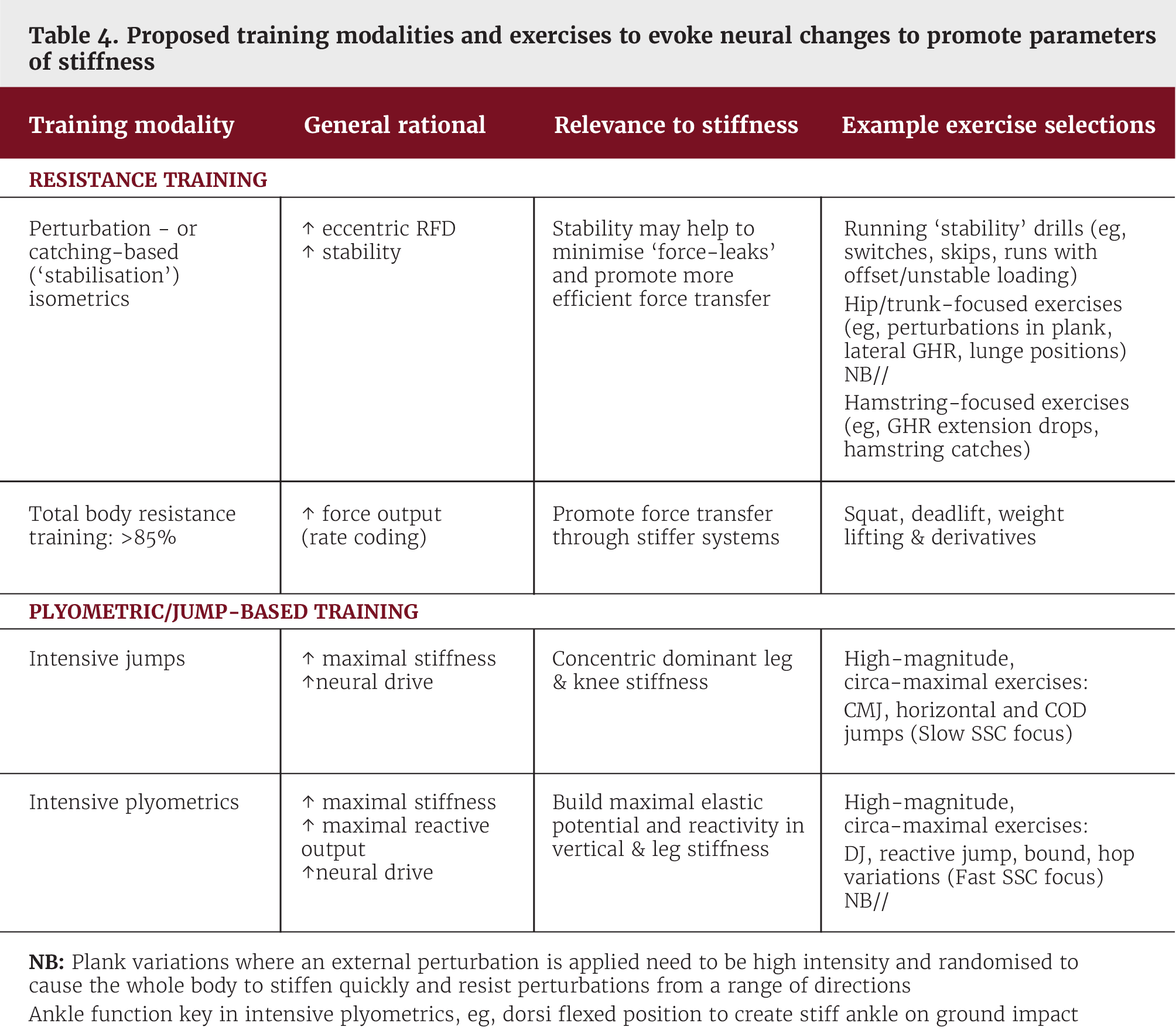

Resistance training interventions have highlighted the role of loading. Malliaras et al34 found that high-load eccentric training (80% of eccentric 1RM) induced greater increases in tendon modulus and stiffness compared to standard or concentric (80% of concentric 1RM) loading, particularly at higher torque levels. Cormie et al12 observed a significant increase in vertical stiffness during countermovement jumps (CMJ) after a 10-week back squat intervention, starting at 75% and progressing to 90% of 1RM. Conversely, Toumi et al54 found no effect on vertical stiffness following a leg press intervention using 70% of 1RM, emphasising the critical role of adequate loading intensity. Similarly, Arampatzis et al4 demonstrated that Achilles tendon adaptations, such as increased stiffness and elastic modulus, were elicited only at higher strain magnitudes (4.72%) during an isometric training intervention. These studies collectively highlight the role of load and strain magnitude in driving adaptations. A more reductionist approach has been used to explore joint-specific stiffness adaptations. Kubo et al27 investigated a 12-week programme comparing resistance training (unilateral calf raises at 80% of 1RM) with plyometric training (hopping and drop jumps performed on a sledge apparatus at 40% of 1RM). Their findings revealed increased ankle stiffness after the jump training but not after the resistance training. Interestingly, Achilles tendon stiffness improved with resistance training, but showed no change after jump training. These results suggest that training adaptations may vary between muscle-tendon units and underline the specificity of loading in stiffness development.

Stiffness may also be affected acutely and, in part, explain post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) responses.35,5 For example, PAPE interventions have been linked to acute increases in stiffness, such as using a weighted vest during warm-ups, which enhanced leg stiffness and subsequent running performance.6 Similarly, incorporating plyometrics in warm-ups has been shown to increase stiffness and improve running performance.55 Interestingly, resistance training shows a mixed response in acutely augmenting stiffness. Back squat protocols at lower intensities, such as 12 repetitions at 37% of 1RM57 or medium intensities like three repetitions at 70% of 1RM,42 and two repetitions at 80% of 1RM,40 had no measurable effect on vertical stiffness. However, high-intensity lifts appear to positively impact stiffness. Moir et al41 demonstrated that performing three repetitions of back squats at 90% of 1RM significantly increased vertical stiffness in a CMJ task. This intensity-dependent response may stem from the relationship between muscle force capacity and stiffness. It is worth noting that the use of back squat on its own to increase vertical stiffness may be problematic. Part 1 of this review showed the importance of ankle stiffness in vertical stiffness squats could train aspects of vertical stiffness tasks, emphasising that plantar flexor force output may be a superior intervention.

Cormie et al12 suggested that increased muscle force capacity is required to enhance muscle stiffness, which in turn raises joint, leg, and vertical stiffness. Additionally, Duchateau et al15 showed that motor unit recruitment improves with loads below 85% of 1RM, but rate coding changes, which acutely boost force output, occur only at intensities above 85% of 1RM. This threshold may represent the minimum intensity required for acute increases in vertical stiffness during resistance training interventions.

Stiffness plays a crucial role in many whole-body actions and aspects of stiffness can be effectively trained. However, the success of any exercise intervention hinges on the objective of the programme, which should guide the coach in targeting the desired adaptations. It should be remembered that shorter ground contact times are generally linked to increased performance in ground reaction based tasks.14 Additionally, vertical stiffness is linked to both shorter ground contact times and increased ground reaction forces.2 Therefore, the ultimate objective of any stiffness intervention should be to minimise ground contact time or contraction time, without compromising force output, or to maximise force output without increasing ground contact time. Although increased lower limb stiffness may be the higher-order objective in this example, coaches should be aware of providing the athlete with an appropriately conditioned ‘chassis’ and well developed ‘engine’ in order for the benefits of a superior ‘suspension system’ to be safely realised.

Ultimately the aim of a programme designed to improve athletic performance should be twofold: to increase propulsive impulse in the intended direction of the performance task, while simultaneously minimising potential injury risk. Injury risk reduction is based on the premise that injury occurs when the magnitude of force applied to a biological structure exceeds its capacity to withstand this force.19 This premise is supported by Lauersen et al;31 their meta-analysis demonstrated that strength training can significantly reduce acute injuries by one-third and chronic injuries by half, while proprioception training can reduce injuries by up to half. Therefore, any intervention to improve stiffness will need to involve strengthening structures and proprioception in order also to potentially positively impact injury risk.

Recommendations for training stiffness depend on whether region-specific stiffness around a joint is required, or more global stiffness increases in either vertical or leg stiffness. Vertical stiffness is particularly relevant for tasks requiring predominantly vertical force production, whereas leg stiffness is more applicable to tasks with greater horizontal force demands.

The training modalities and exercises presented below are not a definitive list but represent scientifically supported conditioning practices widely used in S&C coaching. They can serve as a useful starting point for coaches aiming to improve performance. However, not all performers will require every training modality, as training needs depend on factors such as past training background, individual strengths and weaknesses, and the specific requirements of their sport. Regular monitoring of the targeted adaptations should inform specific programme design and length.

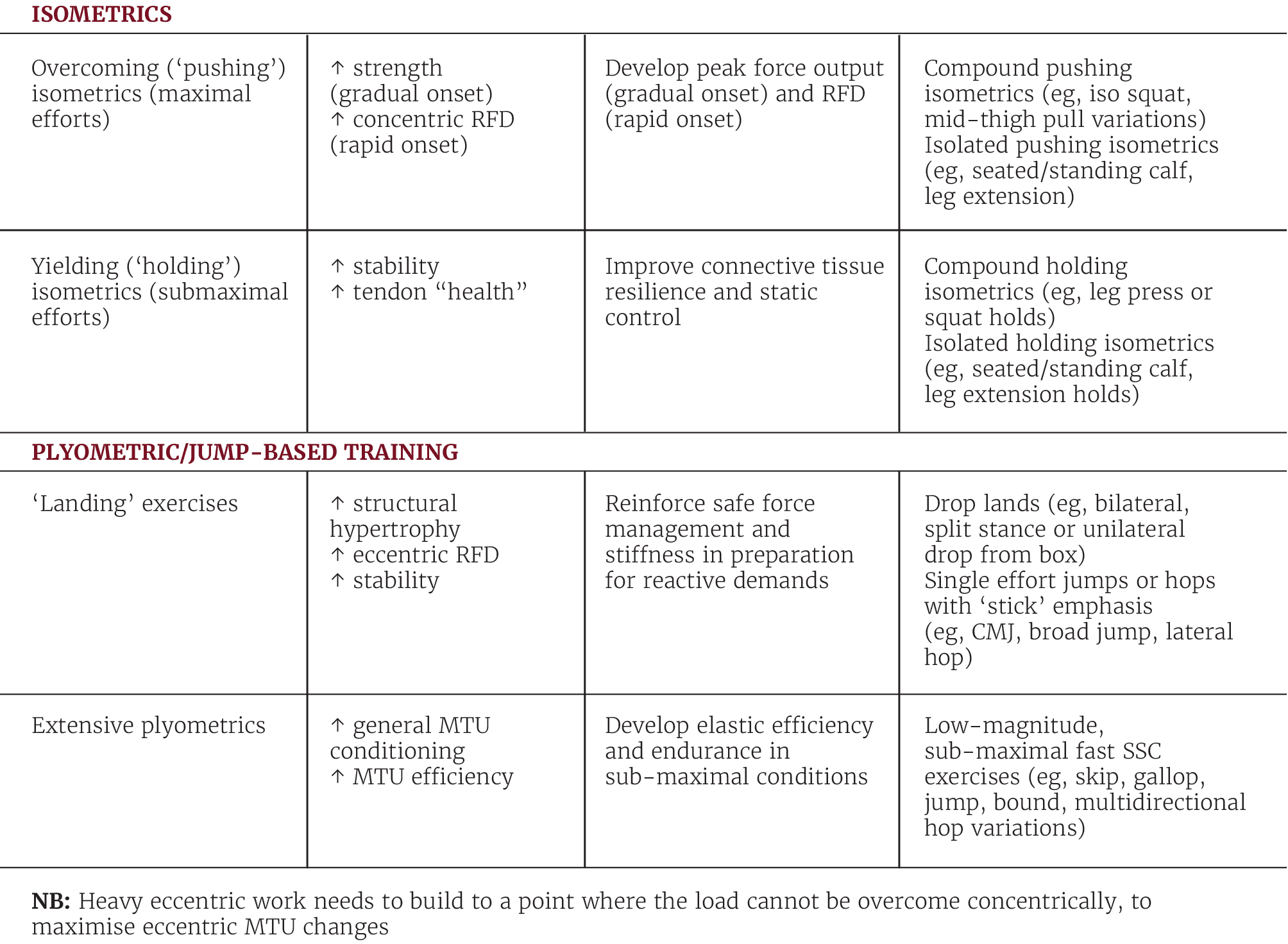

Structural adaptations lay the foundation for the body’s systems to stiffen effectively under load and form the basis for reducing injury risk. Thus, when structural changes are needed to enhance stiffness, it is recommended that these be prioritised early in any programme. The sequence of exercise modalities outlined here is recommended within a linear periodised plan; of course, this is not to say that this is the only approach that coaches can effectively employ.

Initially, it may be prudent to emphasise some combination of heavy resistance training, slow eccentric training, isometric training, and extensive plyometrics to build the capacity of the MTU to handle load. These preparatory exercises ensure the systems are equipped to progress to faster eccentrics and landing drills, where managing ground reaction forces becomes a critical focus. Resistance training and heavy eccentrics should be performed to near failure to drive anatomical adaptations, particularly for structural and hypertrophic changes. Isometric exercises can play an important role in this process but should be tailored to the intended outcome.49,33 Yielding (or ‘holding’) isometrics are particularly effective for stability and tendon remodelling, probably due to the tendon creep induced by longer-duration holds.50,40 These exercises are ideal for enhancing connective tissue resilience and preparing the MTU for dynamic loads, but demonstrate the potential to impair stiffness if prescribed in isolation. In contrast, overcoming (or pushing) isometrics are more effective for developing stiffness, particularly when performed with a rapid onset (ie, maximal explosive intent) and short (<6 sec) durations.

It is important to note that maximising efficiency and performance in human movement relies on the active component of the MTU functioning quasi-isometrically. This allows the passive component, particularly the tendon, to stretch and recoil effectively. Strength training at this stage can enhance the tendon’s contribution to the MTU performance.30 Additionally, accentuated eccentric training provides the high loading tendons need to achieve meaningful changes in tendon structure and function.4

Once the required structural changes have been established, training may shift focus toward neural and coordination adaptations. Notably, resistance training should increase in intensity within the primary exercises of the programme; although squat, lunge and deadlift variations can be used, a shift towards more velocity-dependent weightlifting actions may be promoted. It is also possible that supplementary exercises in the programme may seek to employ greater coordinative and stability challenge: for example, prescribing drills with external perturbations or reflexive catches. These types of exercises require the athlete to stiffen structures in response to rapid changes in loading conditions.

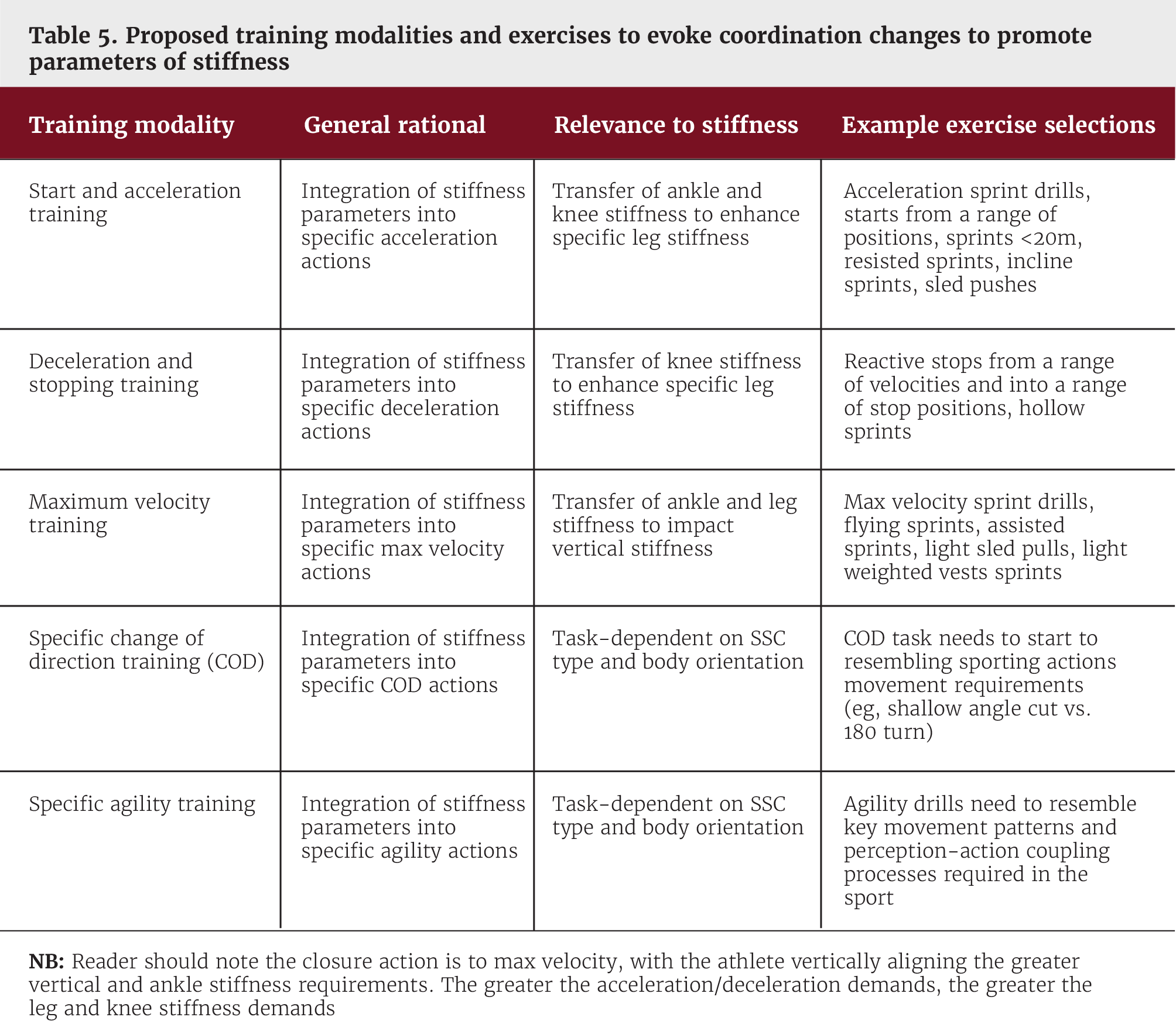

As the programme progresses, coaches may consider the implementation of more intensive plyometric exercises. Plyometric training, including exercises such as jumping, bounding, hopping, and sprinting, becomes more important as the intensity of SSC actions rises, necessitating greater stiffness for optimal performance. Key to effective plyometric training, whether slow or fast SSC, lies in considering both the time taken to complete each movement, together with the height or distance achieved. It is imperative that increases in height or distance are not accompanied by longer durations as this would hinder the development of stiffness. Additionally, if metrics such as jump height or distance does not increase, but ground contact time or contraction time decrease, this would signify a positive stiffness adaptation.

Stiffness is a product of the viscoelastic and structural properties of joints, MTU and connective tissue;32 however, it is also the coordination of these passive and active components requiring optimum limb positioning, pre activation, stiffness and timing to produce impulse in an appropriate direction, thereby achieving a fast and effective desired performance outcome. The initial structural and neural training is designed to train different aspects of stiffness as a physical quality. Performers should have an increased ability to stiffen structures appropriately under load, but the application of stiffness is a context-specific skill. This process has been grouped under the idea of coordinative adaptations. Here, we suggest a simple to complex approach, where training starts with linear sprinting movements before progressing (if required by the demand of the sport) to multi-directional work and agility performance. It must be remembered that human biological systems will learn to self-calibrate to apply appropriate stiffness solutions to a variety of performance challenges,23,24 as long as those systems have the capacity to cope with the forces applied to them and the chosen movements are coached adequately. However, discussion of how to coach these skills is beyond the scope of this review.

Although these training recommendations are presented in a logical order, which may appeal to a coach using them in a linear periodised plan to maximise a specific outcome, they can just as easily be included in a more conjugated plan; this would train all aspects of stiffness, with key aspects promoted based on a performer’s weaknesses or the period of the season you are working in. The presented training has a wide variety of potential interventions, which is recommended as performers have individual needs, with training variety shown to help improve performance and mitigate injury risk.17

The precise measurement of stiffness is beyond the scope of many coaches. However, coaches should understand that stiffness is not a performance variable itself, but rather a measure of how an athlete achieves a performance outcome. To assess stiffness effectively, it should be considered alongside performance metrics (eg, jump height or sprint time) and in relation to normative data or longitudinal changes. Practical monitoring of stiffness can be done by tracking temporal outcomes, such as jump or sprint times and ground contact or contraction time durations. Observing changes in joint or centre of mass dynamics during the SSC actions can provide coaches with further information to inform the training process. Changes in performance, such as increased impulse with unchanged ground contact times, can indicate enhanced stiffness. Field-based tests provide valuable insights – as long as test conditions are standardised to ensure reliable results. These methods, although subjective, offer accessible and cost-effective tools for coaches to monitor and guide training adaptations. Measures of lower limb stiffness can be improved through various training interventions, including resistance and plyometric training. Although specific training interventions should be tailored to the individual athlete and the demands of their sport, this review has outlined a progressive-based approach to the development of stiffness in order to enhance sporting performance through sequencing structural, neural and coordinative-based objectives. This framework is intended to provide S&C coaches with some guidance for developing stiffness as part of a holistic training programme.

Iain has worked in the field of sport and exercise science for over 35 years with a range of with a range of sports organisations, including the English Institute of Sport, the FA, England Rugby, Northampton Saints, Northampton CCC and Luton Town. In his university role, Iain leads the BSc and MSc courses in S&C, with particular research interests in the use of biomechanical principles to optimise human function and performance.

Sean is the founder of Maloney Performance, a high-performance strength and conditioning service supporting athletes and teams across multiple sports. He also leads Palestra Education; a coach development initiative focused on translating sport science and pedagogical principles into practical learning.