By Callum Blades, MSc, CSci, MCASES, ASCC, CSCS, RSCC, School of Sport and Exercise Science, University of Derby

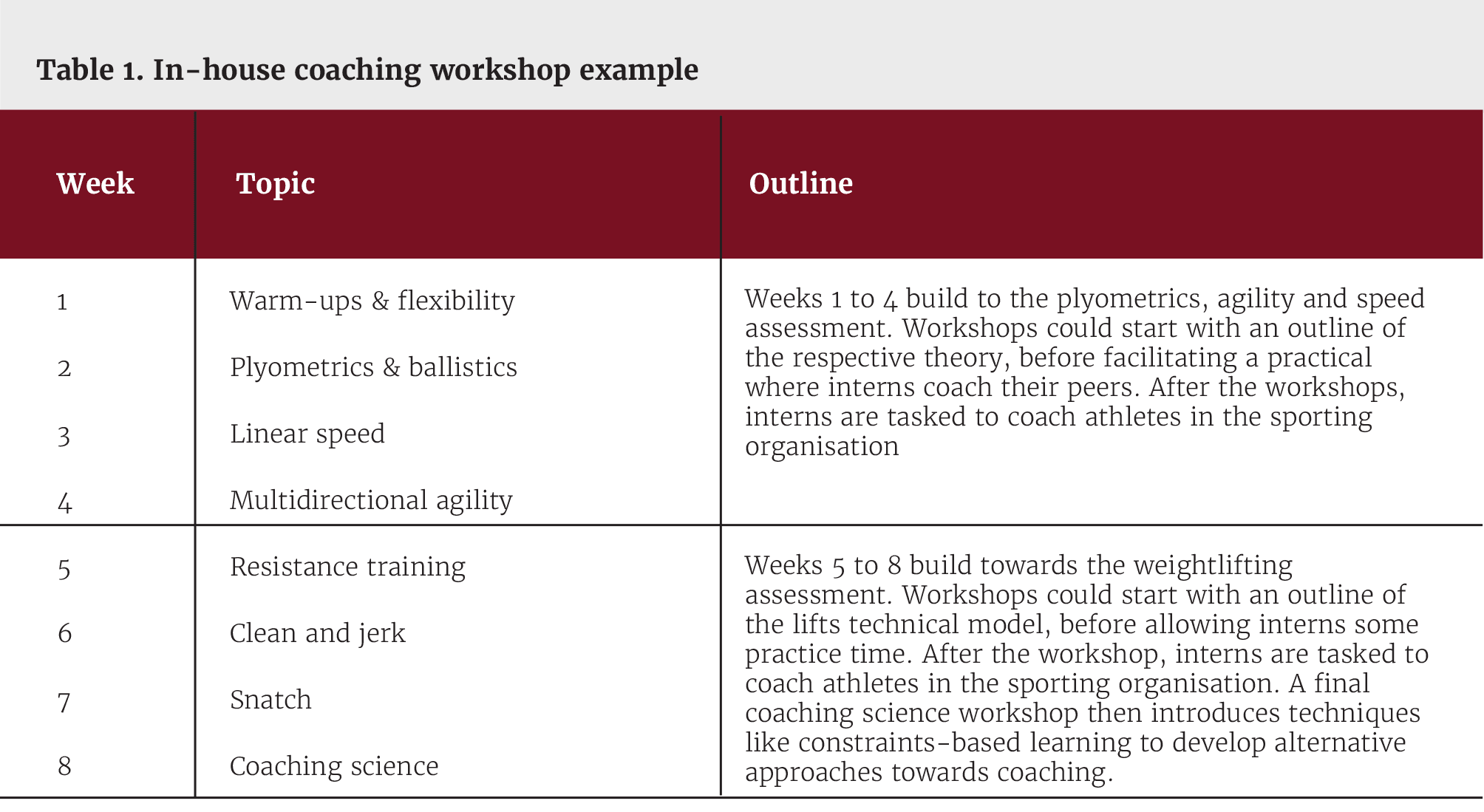

Internships are vital for preparing early career strength and conditioning (S&C) coaches for employment. S&C coaches must possess professional qualifications, have accrued years of experience, and demonstrate various knowledge, application and interpersonal skills. Therefore, in designing effective internships sporting organisations should consider recruitment strategies, the internship’s legal status, in-house professional development opportunities, and the internship structure from induction to exit interview. This article considers each of these areas with the aim of providing sporting organisations with up-to-date guidance on designing effective S&C internships.

Internships form an essential part of S&C coaches’ early career development.2,10,11 These opportunities provide interns with practical experience and the chance to assess their career trajectory under the guidance of a mentor.2,10 However, sporting organisations also benefit through recruiting an intern with high potential that they can develop, as well as creating an extended probationary period to assess the fit of a potential hire within their organisation.2,10 To maximise these potential benefits, it is essential the internship is well designed and considers how it will effectively enhance the employability of the intern.2,10

The starting point for designing an internship is an understanding of the minimal requirements for gaining employment within the S&C industry.17 The internship can then be reverse engineered in the same way that S&C coaches would use a sport-specific needs analysis to inform training programme design. There must also be a distinction between either a curriculum-based work placement or graduate internship, depending upon whether an intern is undertaking the internship to achieve a higher education qualification. This enables an effective internship to be designed for the benefit of the student, employer and, where applicable, university.

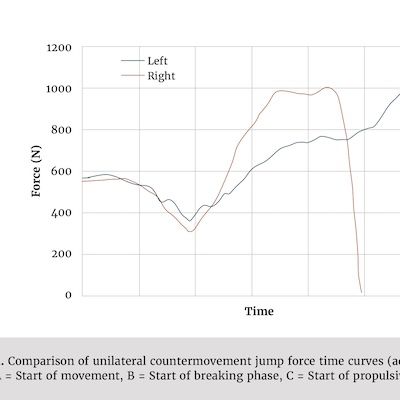

Key factors required for employment within S&C include higher education qualifications, professional qualifications, years of experience and the development of skills (Figure 1). The majority (73%) of S&C job descriptions list a bachelor’s degree within a sports science-related field as essential, with a master’s degree outlined as desirable on 27% of occasions.17 Certification from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) is the most commonly (45%) sought professional accreditation, followed by the UK Strength and Conditioning Association (UKSCA) on 29% of occasions. However, the cited study used NSCA, UKSCA, LinkedIn, Indeed.com and Glassdoor.com jobs boards because no vacancies were available on the Australian Strength and Conditioning Association (ASCA). If vacancies were available via the ASCA jobs board, then increased regionality may occur around the professional accreditation being sought. Sporting organisations also required one to two years of experience, but 63% of the job descriptions did not define what areas this was required within (eg, senior or youth athletes).16

The skills required within job descriptions can be subdivided into knowledge, application, interpersonal and other.17 The most common essential knowledge skills (69%) were programme design, with management/leadership and IT being essential within 29% of job descriptions. Application skills considered essential included session delivery (84%), testing (51%) and data analysis/reporting (39%). The interpersonal skill most listed as essential was teamwork (53%), with educator/mentoring required within 37% of job descriptions. Lastly, the other skills of note were knowledge of the sport, research within S&C, injury/rehab and nutrition. The required skills are likely to change in importance depending upon the seniority of the role being advertised. Future research should quantify how required skills may change, as this was unclear within the cited study.

Internships must address these general key factors to ensure that interns are employable within the S&C industry. However, each sporting organisation will require S&C coaches to apply these specifically based upon their unique environment. For example, within professional football clubs, the S&C coach must adopt scientific principles to devise and deliver training programmes that enhance players on-field performance and reduce their likelihood of injury.16

S&C coaches may also need to take a holistic approach towards training monitoring and recovery to ensure players achieve optimal readiness to perform in matches. Each sporting organisation must therefore take responsibility for developing an internship that creates a learning environment and addresses these specific demands, as well as the general key factors required for employability within the S&C industry. For example, undergraduate students, on a curriculum-based work placement, may prioritise developing programme design and session delivery. In contrast, recent postgraduates, on a graduate internship, may develop educator/mentoring skills by supporting undergraduates.

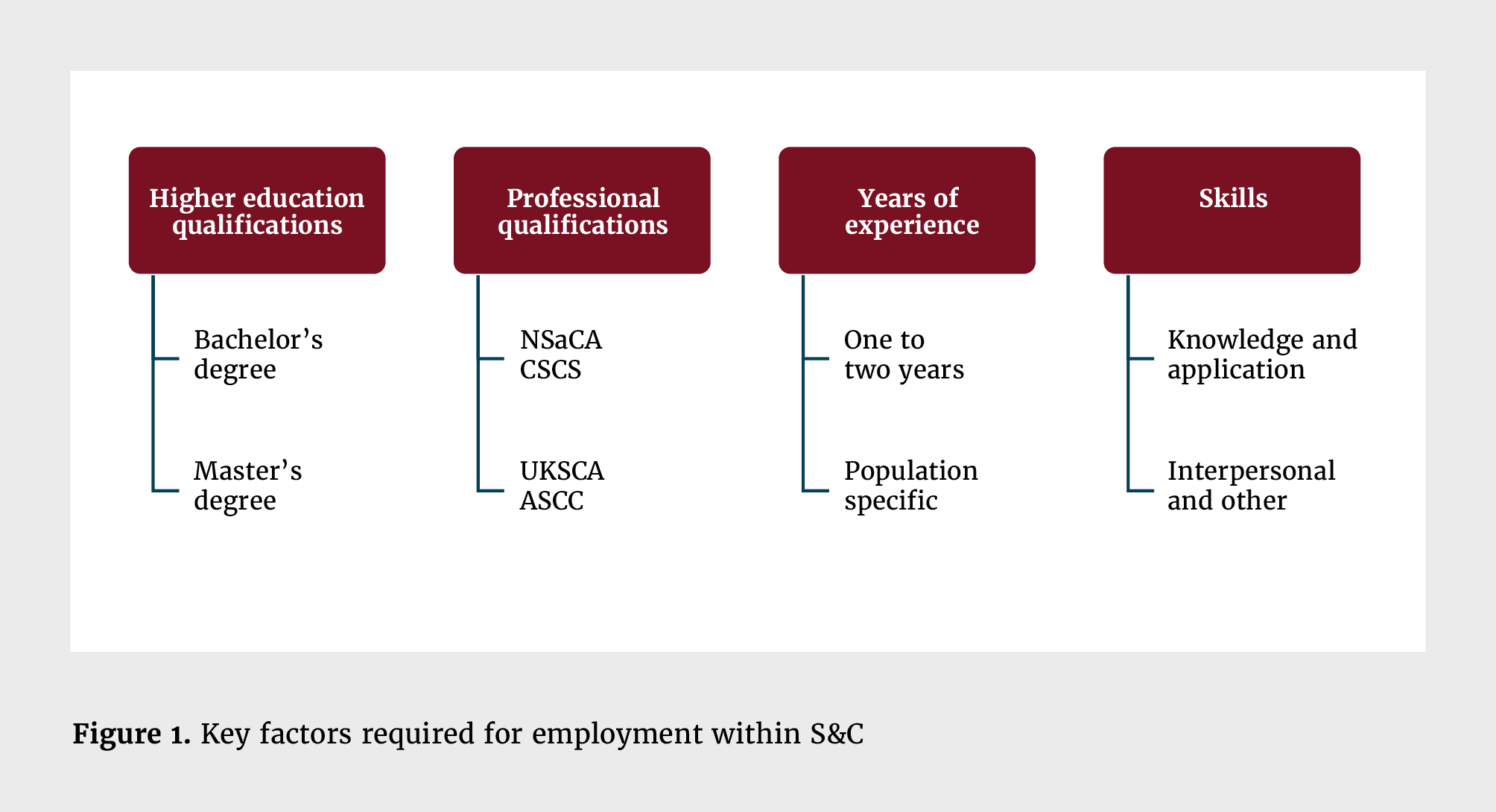

An internship should be designed with input from stakeholders across the sporting organisation, while at the same time being mindful of what the potential interns’ knowledge and skillset is likely to be at entry. Collaboration with universities is also required when interns are undertaking the internship as part of their academic requirements. This collective input should be used to scope the internship and any associated expectations, which can then be used to inform the recruitment process (Figure 2).

The recruitment process should reflect the sporting organisation’s recruitment policy to maximise the likelihood that interns will integrate well into the organisation.2 Traditional recruitment processes required a curriculum vitae and cover letter during initial screening, which was followed by a formal interview with the selection panel.7 However, modern initial screenings may include video pitches, with the formal interview encompassing oral presentations and/or practical tests.7 It is therefore imperative that sporting organisations review their recruitment policy to reflect up-to-date practices that maximise the likelihood of identifying suitable interns.

Caution is advised when using video pitches, as they indicate an intern’s visual appearance and discernible characteristics. In a commitment to equality, diversity and inclusion, organisations should consider whether initiatives can be used to encourage applications from under-represented populations. These initiatives may cover inclusive marketing and targeted outreach when promoting the internship, alongside anonymised initial screening and diverse selection panels for formal interviews. Each S&C coach has a unique experience of course, but interviewed female S&C coaches have reported that ‘people often think you’re a physio, not that you’re there as an S&C coach’.3 Females, alongside other underrepresented populations in S&C, should be clearly visible in sporting organisations to promote balanced perspectives.14

Another key consideration during the recruitment process is whether interns are in the process of completing a higher education qualification or have already completed one. Completing a bachelor’s degree, as a minimum, is essential to meet the first key factor required for employment within S&C.18 Importantly, whether a potential intern is completing or has completed their bachelor’s, or master’s degree, could have important legal repercussions for whether the internship is categorised as a curriculum-based work placement or graduate internship respectively. This categorisation is vital because it determines an intern’s entitlement to core employment rights and to being paid the national minimum wage.

When interns are in the process of completing a higher education qualification, the internship may be considered a curriculum-based work placement. This forms part of a programme of study where it is embedded within a framework of learning outcomes, like those of an academic module.1 A placement learning agreement signed by the student, sporting organisation and higher education institution would be considered best practice. This agreement should outline the start and end date and number of learning hours, which should be linked to the credit value of the student’s academic module. These learning hours should include pre-placement preparation time, contact time with the sporting organisation and reflection time.

The agreement should also include contact details for all three parties involved, supervisory arrangements, learning objectives and outcomes that are associated with the academic module as well as any evaluation process that will occur during and after the placement. Students undertaking a curriculum-based work placement for up to one year are exempt from receiving core employment rights or being paid the national minimum wage.1,2

In contrast, when potential interns have completed their higher education qualification, then taking them on may be considered a graduate internship.15 Classifications include either a volunteer, worker or employee, depending upon various circumstances. A volunteer has no contract of employment and thus is under no legal obligation to perform work. Only legitimate expenses incurred during their volunteering should be reimbursed, such as the cost of travel. Workers are anyone undertaking work on behalf of an employer, either under a contract of employment or any other similar agreement. As there is an obligation to perform work, they are entitled to core employment rights and protections. Lastly, an employee is anyone working for an employer under a contract. Employees are entitled to the same employment rights and protections as workers, but they must also be paid the national minimum wage.15

Sporting organisations must therefore consider carefully whether they are operating a curriculum-based work placement or graduate internship. Recruiting an intern who will receive little or no remuneration – which is just based on their own goodwill or because there is demand for such internships – may be against the law and is likely to provide neither party with much benefit.2 Instead, internships should be linked to a specific role within the sporting organisation and professional development opportunities should be offered, so that interns can progress into these roles.10 In general, curriculum-based work placements should be unpaid and graduate internships should have a guideline annual salary of £17,500 to £20,500.12

Continuous professional development (CPD) opportunities are essential for the growth of S&C coaches.5 Formal CPD typically follows a core curriculum, which culminates with standardised assessments that evaluate learners’ competence against set learning outcomes. Informal CPD encompasses mentoring, observation, reading and peer group discussions, which are largely self-directed and informed by a learner’s perception of their needs. Non-formal CPD includes broad-ranging activities like attendance at conferences and clinics, which are formally organised but sit outside of formal CPD curriculums. Within an effective internship there is scope to incorporate all three CPD opportunities.

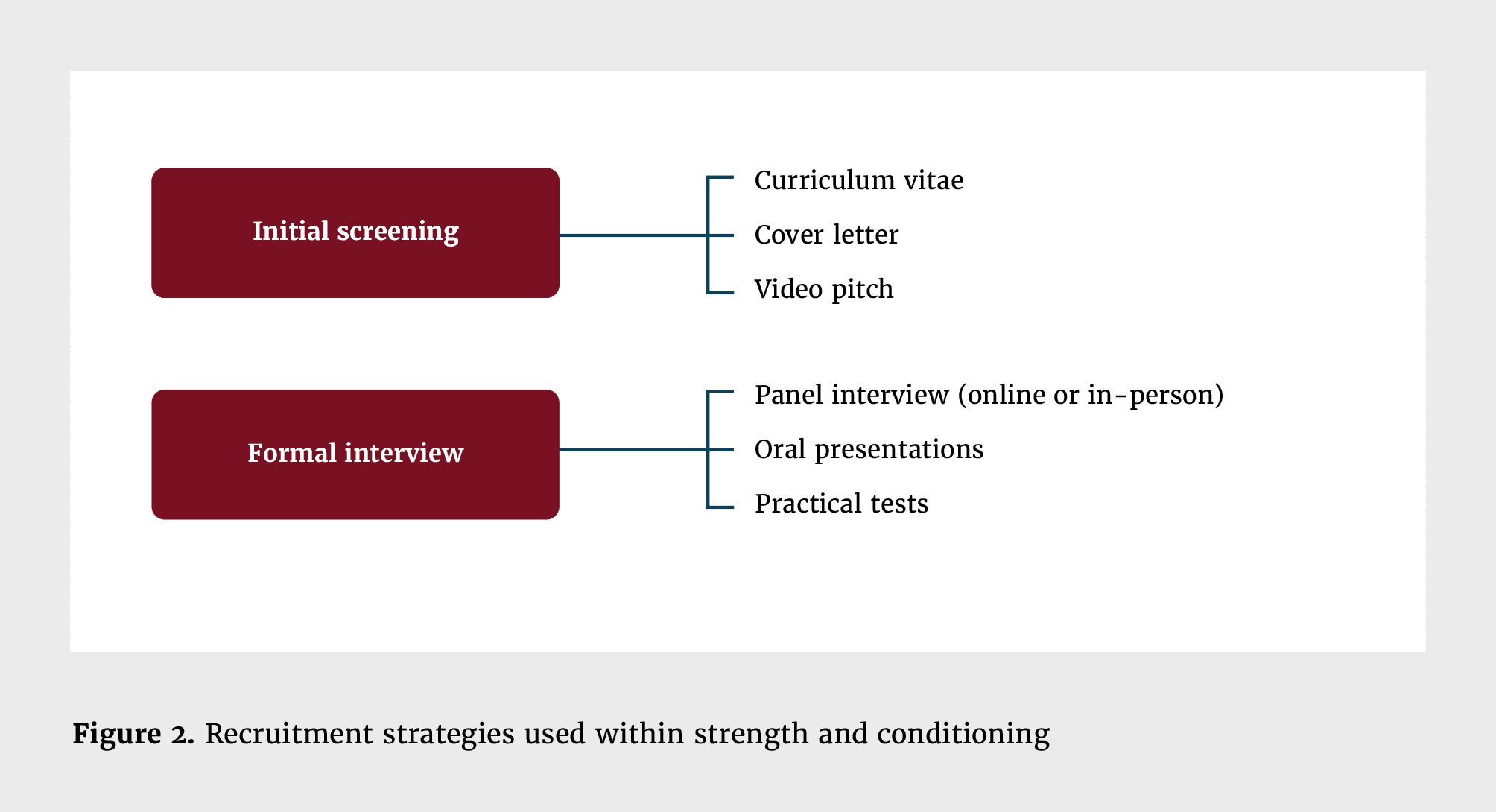

The second key factor for gaining employment within S&C was professional qualifications, so this forms a logical starting point for designing formal CPD opportunities.18 If the formal CPD builds towards the UKSCA Accredited Strength & Conditioning Coach (ASCC) for example, then the ASCC competency document could be used to provide the core curriculum. In-house workshops can then be used throughout the internship to cover this core curriculum and build towards the four UKSCA ASCC standardised assessments. A block of eight coaching workshops is proposed that prepare interns for the plyometrics, agility and speed assessment and weightlifting assessment (Table 1). Another block of eight programming workshops is proposed to prepare interns for the multiple-choice examination and case study presentation (Table 2).

Informal CPD is largely self-directed, using activities like mentoring, observation, reading and peer group discussions.8 These informal activities can build upon formal CPD workshops to further develop the knowledge, application and interpersonal skills required for gaining employment within strength and conditioning.18

The knowledge skills most frequently requested by job descriptions, which are appropriate for development within internships, were programme design and IT.18 Programme design skills are developed formally across the programming workshops, where interns are supported to plan periodisation strategies and design training sessions. These skills could then be further developed informally with mentoring from a senior peer in the sporting organisation. IT skills will be formally developed within the athlete monitoring workshop by tasking interns to process data using the preferred systems of the sporting organisation like Microsoft Excel. Interns could then informally diversify these skills by reading around other systems such as R or Power Bi. The sporting organisation could then choose to provide a brief and anonymised data set, which the intern could be challenged to process for the benefit of both parties.

The application skills most demanded for S&C employment, which are appropriate for development within internships, were delivery, testing and data analysis/reporting.18 Delivery skills are formally developed throughout the coaching workshops, where interns must coach exercises across different training modalities. Observing and reflecting on sessions within the sporting organisation would then enable interns to build upon this knowledge informally. Testing skills are formally learned through the needs analysis and testing workshop, where interns must propose a testing battery suitable for their case study athlete. Interns could then be directed towards readings that they can review informally to deepen their formally acquired knowledge. Data analysis skills would be formally covered within the athlete monitoring workshop by tasking interns to process data collected by the sporting organisation. These skills could then be built upon informally through mentoring where senior peers support interns to continue working with data across their internship.

The interpersonal skills in-demand for S&C employability, which are appropriate for development within internships, were teamwork and educator/mentoring.18 Teamwork skills could be developed informally through peer-discussion groups, where interns discuss topics of interest to the sporting organisation with the aim of producing practical solutions to real world challenges. Educator/mentoring skills can also be developed by mentoring, where more experienced interns are partnered with less experienced interns to share their knowledge.

Non-formal CPD is formally organised, but unaligned to a formal curriculum or standardised assessment.8 Examples include conferences and clinics, which typically have specific themes that enable interns to target their attendance based upon any knowledge or skillset gaps. These non-formal activities are perfect for expanding other skills that are vital for employment in strength and conditioning, including knowledge of injury/rehab, nutrition and the sport.18 Depending upon the breadth of the multidisciplinary team, non-formal CPD could be effectively delivered through practitioners taking turns to lead clinics about their professional area for all staff and interns within the sporting organisation. This can offer a key source of CPD for interns, as well as practitioners across the whole sporting organisation.

Knowledge of injury/rehab could be effectively showcased by physiotherapy or sports therapy staff, who could present case studies of their rehabilitation work in a case conference format. Nutrition staff can provide educational sessions around the fundamentals of nutrition and supplementation. Knowledge of the sport could be delivered by sports coaches or performance analysts leading clinics that outline fundamental technical and tactical principles of their sport. These non-formal clinics provide effective CPD for all staff within the sporting organisation, whilst also simultaneously introducing the interns to effective interdisciplinary teamwork.

Knowledge of S&C research could be enhanced through providing interns with the opportunity to undertake their bachelor’s or master’s degree dissertation within the sporting organisation. Working collaboratively between the intern, sporting organisation and university, research projects could be created that will positively impact the sporting organisation’s practices. This could lead to the creation of funded studentships, which provide a fantastic way for interns to gain industry experience, sporting organisations to answer questions and universities to share expertise. For such studentships to be successful, a clear research question should be identified that is within the potential skillset of the intern, of interest to the sporting organisation and in alignment with the expertise of the university.

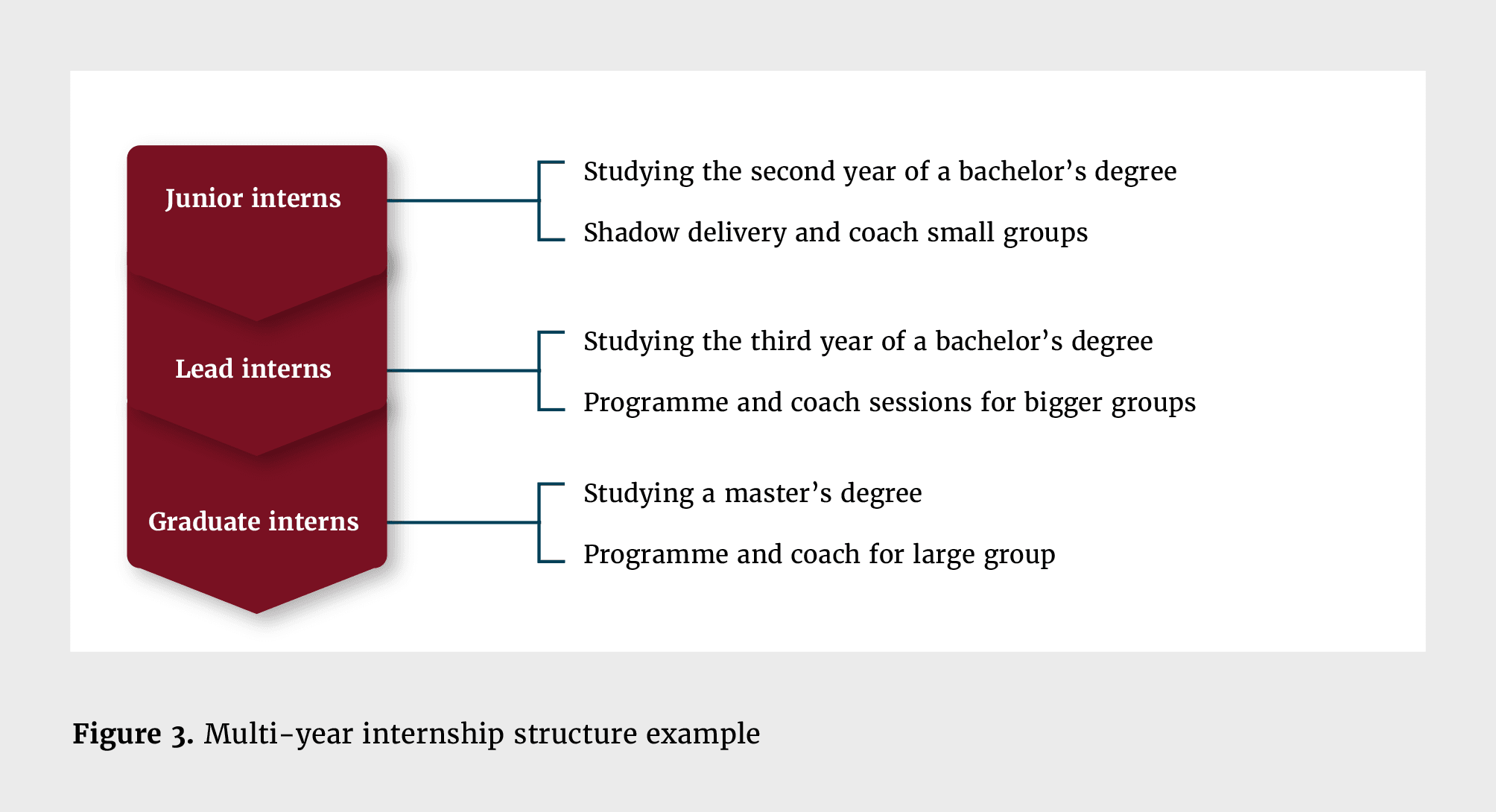

Professional development opportunities should be complemented by applied experience within the sporting organisation. This enables interns to accumulate the one to two years of experience that is frequently requested for S&C employment.18 Individual internships typically range from a few weeks to as long as 12 months, depending upon the needs of both the intern and the sporting organisation.2 However, sporting organisations can explore structuring different internships across multiple years to provide a progression pathway (Figure 3). An example of this occurs in university sport using the junior, lead and graduate intern model.13 Junior interns are studying the second year of a bachelor’s degree and begin by shadowing S&C delivery, before being given responsibility to coach small groups. Lead interns are studying the third year of a bachelor’s degree and are challenged to programme the sessions that they will deliver to bigger groups. Graduate interns are undertaking a master’s degree and can assume responsibility for programming and coaching large groups of higher performing athletes. Although this structure may not be practical for every sporting organisation, it could be worthwhile exploring how curriculum-based work placements at bachelor’s and master’s degree level can provide a progression pathway for interns.

All internships should begin with an initial meeting between the intern and mentor.11 The mentor should outline expectations for punctuality and professional behaviour, before detailing any roles and responsibilities the intern will be assigned.10,11 Well-designed internships empower interns from the outset so they can positively contribute towards the sporting organisation.2 Interns should also use this initial meeting to discuss any personal goals, such as completing their degree, learning about the profession or enhancing their employability.11 The mentor could then develop these goals through conducting a skills audit that identifies skills gaps, which may include the technical components or wider employability skills such as analytical thinking, communication, accepting criticism and time management.2 This initial meeting should occur alongside a wider organisational induction before the internship begins. It is also imperative that colleagues understand the intern’s role.2

Ongoing constructive feedback should be offered by the mentor, which challenges interns to achieve their personal goals.10,11 This feedback should be provided in regular performance reviews where further development objectives can be established.10 Interns should also take responsibility for maintaining a reflective diary that documents their progress.2 They should be encouraged to use an established model of reflective practice and seek feedback from their mentor and peers.8 In general, these models start with a description of the experience, encourage a reflection on what happened and consider any influencing factors.4 Models will then go on to review what could have gone better, before identifying learning points to action in the future.4 The reflective diary could then be discussed during a scheduled exit interview after the internship has finished. This also provides an opportunity for two-way feedback, where the mentor can recommend further development opportunities and the intern can offer insight on how the internship might be improved.2

Internships are a critical component of enhancing the employability of early career S&C coaches and should not be viewed as a cheap employment option. An internship should be designed to enable the achievement of professional qualifications and years of experience, as well as proficiency in knowledge, application and interpersonal skills. Sporting organisations should use up-to-date employment practices to recruit interns and consider if initiatives could be used to encourage applications from underrepresented populations. This recruitment must reflect whether the internship is a curriculum-based work placement or graduate internship, as this has important legal repercussions regarding core employment rights and the national minimum wage.

Formal, informal and nonformal CPD opportunities should then be provided that support the intern’s progression towards becoming employable within S&C. CPD should be complemented by well-structured practical experience, which enables interns to apply their knowledge within a real-world setting. The process should be supported by regular meetings between the intern and mentor, wider organisation inductions, ongoing feedback and reflective practice. When these processes are adhered to, internships can provide valuable benefits to both the intern and sporting organisation.

1. Board, L, Caldow, E, Doggart, L, et al. The BASES position stand on curriculum-based work placements in sport and exercise sciences. The Sport and Exercise Scientist 6–8. 2014.

2. Brannigan, J. Internships: how these should work in strength and conditioning. Professional Strength and Conditioning 28–30. 2016.

3. Craft, V. Coaching spotlight: diversity in team can only help, not hinder, performance. Professional Strength and Conditioning 23–28. 2024.

4. Finlayson, A. Reflective practice: has it really changed over time. Reflective Practice 16: 717–730. 2015.

5. Grant, M, Dorgo, S, and Griffin, M. Professional development in strength and conditioning coaching through informal mentorship: A practical pedagogical guide for practitioners. Strength Cond J 36: 63–69. 2014.

6. Heimann, J. Evaluating the constraints led approach and its application within strength and conditioning. Professional Strength and Conditioning 7–13. 2020.

7. Ingham, S. The First Hurdle. London: Simply Said. 2020.

8. Jeffreys, I. The five minds of the modern strength and conditioning coach: The challenges for professional development. Strength Cond J 36: 2–8. 2014. Available from: www.nsca-scj.com

9. Jeffreys, I. RAMP warm-ups: more than simply short-term preparation. Professional Strength and Conditioning 17–23. 2017.

10. Jeffreys, I and Close G. Internships – Ensuring a Quality Experience for All. Professional Strength and Conditioning 23–25. 2012.

11. Kraemer, W and Nitka, M. Mentoring Future Strength and Conditioning Coaching Interns. Strength Cond J . 2024.

12. Langford, A, Flannagan, A, and Bird, S. Remuneration Guidelines for strength and conditioning coaches within universities in the United Kingdom: International Universities Strength and Conditioning Association (IUSCA) position statement. International Journal of Strength and Conditioning 1: 1–3. 2021.

13. Martens, D. A reflection on three years of internship at Sheffield Hallam University. Professional Strength and Conditioning 9–13. 2020.

14. O’Malley, L and Greenwood, S. Female coaches in strength and conditioning—why so few. Strength Cond J 40: 40–48. 2018.

15. Pye, M, Hitchings, C, Doggart, L, Close, G, and Board, L. The BASES position stand on graduate internships. The Sport and Exercise Scientist 1–3. 2013.

16. Springham M, Walker, G, Strudwick, T, and Turner, A. Developing strength and conditioning coaches for professional football. Professional Strength and Conditioning 9–16. 2018.

17. Vernau, J, Bishop, C, Chavda, S, et al. An analysis of the minimal qualifications, experience and skill sets required for S&C employment. Professional Strength and Conditioning 7–17. 2021.

18. Vernau, JW, Bishop, C, Chavda, S, et al. An analysis of the minimal qualifications, experience and skill sets required for S&C employment. Professional Strength and Conditioning 7–17. 2021.

S&C Coach and lecturer, as well as the lead pathway S&C coach for Birmingham Panthers, Callum has supported athletes at Aston Villa, West Bromwich Albion and Walsall Football Club, in addition to at Coventry University, the University of Wolverhampton and the Talented Athlete Scholarship Scheme.