By Isaac O Hay1, Louis P Howe2 and Rik W Mellor1

1 School of Sport, Exercise & Applied Science, St Mary’s University, Twickenham; 2School of Sport, Rehabilitation & Exercise Science, University of Essex

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterised by significant and persistent impairments in social interaction, communication challenges, and repetitive behavioural patterns. Individuals with ASD often experience difficulties in receiving, processing, analysing, and storing information, necessitating population-specific approaches in various aspects of their lives, including physical development and coaching.

This paper aims to provide strength and conditioning (S&C) coaches with a comprehensive and practical framework for supporting the physical development of autistic individuals. The content begins with an in-depth exploration of autism, its defining characteristics, and common co-occurring conditions or dual diagnoses. This foundational knowledge is crucial for coaches to understand the unique needs and challenges faced by their autistic clients.

The paper then progresses to discuss effective coaching strategies tailored specifically for the autistic population. It looks at how to manage and accommodate the social, emotional, and physical differences that may arise during training sessions. By highlighting these aspects, the paper should hopefully equip S&C coaches with the tools to create inclusive and supportive training environments for the autistic population.

Autism or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is described as a significant and persistent impairment in social interaction, unusual or delayed communication and repetitive behaviour activities.20 Due to difficulties receiving, processing, analysing, and storing information, population-specific measures for coaching autistic individuals must be considered to optimise the coaching process.14 S&C coaches who provide support for this demographic must therefore possess a clear understanding of the symptoms of autism in order to adjust their coaching accordingly.

Autistic people are rarely considered within S&C literature and as a result, little information exists to support the S&C coach. The aim of this review is to provide a brief analysis of available research relating to training autistic individuals of all ages, with a primary focus on the practical implications for the S&C coach to assist in the design and implementation of an effective training process for autistic people.

Autism is a lifelong spectrum condition, ranging in severity from person to person. It affects an estimated 1 in every 160 children16 and, although less common in adults, diagnoses amongst older populations are increasing due to expanding awareness. It is important to consider that not every autistic person is diagnosed, and thus recognising autistic traits can be key to improve coaching effectiveness and inclusivity. Serdarevic and colleagues39 found that identifying low muscle tone in infants might be a gateway to early diagnosis of autism, highlighting the potential physiological differences between autistic and non-autistic individuals. Although low muscle tone has been found to be a good indicator of autism, the criterion for diagnosis is divided into two categories: social deficits and emotional deficits. Social deficits include difficulty understanding verbal communication, eg, tone of voice, and non-verbal communication, eg, body language, as well as difficulty developing relationships with others. Emotional deficits involve repetitive patterns of behaviour, dislike of change, restricted interests, and repeated motor movements, eg, hand flapping or body rocking. The autism spectrum is not merely a question of being more or less autistic: language, motor skills, executive functioning, perception, and sensory processing are all affected to different degrees. Therefore, autism creates challenges that range from severe difficulties to mild and potentially unrecognisable difficulties to untrained practitioners. One example of a social impairment is ‘face blindness’6,34 or, to a lesser degree, difficulty understanding and reading emotional cues emitted via the face. This may include difficulty understanding if someone is happy, sad, or angry, for example.

Autism can create barriers resulting in significantly reduced participation in exercise and sport, often leading to significant health risks.26, 40 This is often due to autistic athletes finding interaction in team sports difficult, resulting in social ‘awkwardness’ and therefore social anxiety.12

Typically, developing adolescents are shown to participate in significantly more moderate and vigorous physical activity than autistic adolescents. Autistic children are 60% less likely to participate in regular physical activity at least three times per week and subsequently are 72% more likely to be obese.26 This lack of exercise results in increased risks of diabetes, higher cholesterol and blood pressure, mobility issues, asthma and mental health conditions.35, 36, 43 Although lack of sporting engagement negatively contributes to the maintenance and development of muscle mass and strength, often autistic individuals already have a lower starting point. The inherent low level of muscle tone (hypotonia), coupled with inherently poor motor planning (planning of movements) consequently leads to lack of motor coordination.10, 28, 32, 37

Often autistic people are hypersensitive or hyposensitive to particular stimuli.12 Sporting environments are highly stimulating and can become overwhelming for them.27 For example, sports halls with poor acoustics may be auditorily overwhelming, likewise playing on a surface with multiple markings for different sports may provide excessive visual stimulation, and playing in muddy or rainy conditions may overwhelm the tactile system. These examples demonstrate the need to tailor the training environment for autistic people to support participation and engagement within an exercise programme.12, 27

Further barriers to exercise can occur due to deficits in vestibular and proprioceptive sensory processing which impacts on balance and coordination.29 A recent ‘Cross Syndrome Comparison’ found significant overlap between ASD and DCD (developmental coordination disorder); it was also found that motor skill proficiency is an accurate predictor of social functioning.42 Therefore, identifying poor motor skill proficiency could potentially be used to help with early diagnosis, which is the most effective way to help autistic people long term.

Because of these DCD-like characteristics, autism may affect perceptual abilities in directly opposed sports,42 such as football or tennis. Poor motor planning or praxis, while not a direct trait of autism, is very common and can result in difficulty with simple tasks such as judging the flight of a ball.42, 21 Johnson-Ecker and Parham13 found that autistic children achieved lower scores in praxis tests than their typically developing peers. DCD is an important area to understand due to the overlapping profiles, and diagnoses can be co-occurring. Therefore, the practitioner needs to understand both DCD and autism when working with this population.

An autistic individual may struggle to ‘read the game’ through difficulty identifying the location and pace of teammates and opponents. Incorrect interpretation of body language may result in difficulty predicting teammates and opponents next moves. Social deficits may impact on their ability to read visual and verbal cues.

This topic is increasingly relevant for S&C professionals as demand for S&C coaches in this field is increasing due to heightened awareness and education regarding specific learning differences, particularly autism. The emergence of events such as the Special Olympics has increased population participation levels,17 leading to more autistic people and those with other learning differences competing in organised sport. However, the Special Olympics is only for people with intellectual functioning (IQ) scores of less than 75 and therefore autistic athletes would not be eligible to enter.

Exercise participation and athletic pursuits have shown to be significantly therapeutic in autistic children;33 however, autism can create barriers to S&C and physical activity participation. When working with an autistic person, individualising the training process is essential for supporting engagement. Individuality5,14 is a factor that all S&C coaches should consider, but it is important to understand that the level of individualisation will be much greater in autistic people than when working with the general population.

Most research around autism is carried out with pre-adolescent populations and while additional needs can be accentuated during this age bracket, the range of individuality and differences is maintained into adulthood. To express the importance of individuality, we must always emphasise that no two children are ever the same and although two children may have the same diagnosis, their needs could be completely different. Therefore, an initial consultation5 is important to understand the individual, their specific needs and how autism affects them. It is important to note that most literature, when stating why a certain aspect of autism may impact sporting performance or participation, most often quickly follows up by stating when exercise programmes are not adapted to their needs.5

A common feature of autism can be obsessional areas of interest20 and when applied in a sporting context, results can be significant. These areas of interest occur often in the field of ‘folk physics’, the understanding of how things work: it is rare that autistic people are interested in folk psychology, the understanding of how people work.4 Common obsessional areas of interest to be aware of are building blocks, trains, cars or other mechanical objects; they also obsess about things that follow clear logical reasoning like mathematics or law. When autistic people are obsessional about sports, results are often groundbreaking: Tom Stoltman, the British professional strongman, is a prime S&C example. Other examples of professional athletes with autism can be found in mainstream, team and individual sports, such as football, baseball, running, surfing and strongman. To reach an elite level in any sport one either needs extreme natural talent, an obsessive desire to practise, an environmental need to practise (eg, having to run to get to school), or – most commonly – a combination of all these factors. S&C coaches may be able to utilise an area of interest to have a positive effect.

Autistic people have significantly more difficulty with emotional self-regulation than the general population, something which is more pronounced in their pre-adolescent years.48 Emotional regulation is something that a well-versed coach can control, but it is important to consider the age of the athlete: the younger the athlete the harder this is to control. During the height of a child's puberty, hormonal fluctuations also make this more difficult. Barriers to participation may not be the sport or activity itself, but a coach lacking understanding of the autistic athlete’s needs.12, 27

A safety consideration when working with autistic people is their potential inability to recognise or understand interoceptive signals – ie, they may not be able to tell if they are too hot or too cold, overheating, dehydrated, or have overexerted themselves.19 Significant consideration for implementing regular drinks breaks will not only help reduce dehydration, but helps to implement structure, something which most autistic people generally prefer. Another interoceptive issue can be the processing of pain or discomfort.8 This includes heightened or decreased sensitivity to pain, and when dysregulated these issues can be amplified. As a coach it is important to be attentive to over or under sensitivity to pain, using one's own discretion and not relying on the athlete for an accurate response. Autistic people may confuse training-induced discomfort with pain and may not be able to tell the difference between the two. It is important when training to manage the athlete's exertion; training to failure may be extremely painful, and comparing how it would feel as the practitioner may not be an accurate method of gauging the athlete’s level of discomfort. Allely found that decreased sensitivity to pain in the autistic population is rare, and that autistic people may just present differently when hurt.2 Therefore, despite the rarity, it is important to be mindful of pain insensitivity, although usually it is the reaction that needs to be understood. Over-sensitivity to pain is much more common.

It is clear there are multiple dimensions to consider when coaching autistic people. This review will now aim to identify, explain and provide coaching adaptations to aid in the coaching process. The three areas that might differ between generic S&C coaching and coaching autistic people are mentioned below; the aim here is not to point out or reaffirm knowledge S&C practitioners already have, but to underpin how a coach's approach to autistic individuals may change. These areas encompass the main differences between coaching autistic people and the general population; they highlight areas that may encourage a degree of re-evaluation around one's coaching methodology. Many coaching methods will be discussed, and although some will be out of the generic realms of a S&C coach, often tactical coaching points present themselves in sessions and it would be remiss of any S&C coach not to make the most of these opportunities.

These three key areas are: coaching environment and methods; communication methods; and modification of exercises.

It is clear that the instruction of autistic people has to differ from the general population and therefore it is important to think ‘outside the box’ when approaching these areas. This means trying to step into the shoes of the autistic person: talking to current or past coaches who have worked with the athlete, as well as therapists or family members, helps in gaining a deeper understanding and interpretation of their individual needs from a S&C and autistic standpoint. This is useful before planning and adapting the session towards any specific areas. It is important that extra care is taken when working with this population as they often lack the sporting and S&C experience you would expect of someone their age.26

Firstly, when working with any athlete there will be things that cannot be controlled, but it is important to have a thorough understanding of what is and what is not a suitable environment in which to coach an autistic athlete. When working with autistic people, an increased effort must be made to control the environment as an autistic athlete with relatively mild difficulties may display more severe difficulties when overstimulated or over aroused.

For many autistic people a one-to-one scenario may be the most effective coaching method; however, when working within team sports this is often impossible. Working with a large group can be challenging as managing multiple peoples’ arousal levels is hard. However, following the guidelines and methods below will help to steady arousal levels, minimise challenging behaviour and improve engagement. One-to-one coaching may well be the best way to start working with an autistic person; however, once they adjust to the new coach, they may be able to tolerate working in a group scenario. Autistic people can be very adaptable, but it is worth remembering that this process may take longer than expected.

A simple way to help improve session engagement is to limit distractions, consider one-to-one sessions rather than groups where possible, as well as limiting noise and the presence of other people. This is not always possible, but the people that might benefit most from this sort of coaching will be those that struggle the most to engage in social or team sports. Limiting noise and the presence of non-essential people within team sport training sessions can be achieved by sessions taking place away from other clubs. Non-essential equipment and visual information should also be minimised. One way to do this is to set up and tidy away each part of the session before moving onto the next. These methods help to control arousal level and avoid overstimulation.

When conducting sessions, bear in mind the autistic athlete’s need for ‘sameness’ and their dislike of change. To help them to cope with real world scenarios, change should be implemented in a controlled progressive manner, not completely avoided. Changes that the general population may not have considered or even noticed can have a significant effect on an autistic person – for example, changing the pattern on a football could provide enough of a distraction to affect the whole session. Ample warning of significant changes such as location may be necessary and a period to adapt to the expected change may help ease the process.

Visiting a new location before attending a session is a tool often used to help settle autistic individuals. As mentioned previously, arousal level and where the individual is on the spectrum dictate which methods are needed. A severely autistic person may need a few days or a week to visit a new training location before feeling comfortable to train there, whereas another person may need no warning or adjustment period. Going through the session plan at the beginning of the session allows the autistic athlete to prepare themselves for change, while the cool-down can be a useful time to talk to and prepare the athlete for the next session.

In any setting (gym, sports hall, track, field etc) auditory, visual, and tactile sensory overload should be considered, as particular stimuli may act as a barrier to participation.12 The S&C practitioner should avoid unnecessary changes in sensory information. Avoiding spaces that are larger than needed can help to reduce distractions. Echoing halls are often unavoidable but the use of ear defenders and avoiding using whistles are some examples of strategies to help with this. Markings on astroturf pitches or halls can often be visually overwhelming as well as confusing. It is vital that all participants know which lines of what colour are relevant to the game or sport they are playing.

The weather should be a consideration as pouring rain may be auditorily dysregulating and a tactile challenge. If the playing surface becomes muddy or wet, this again can be a challenge for the tactile system. The practitioner here should consider completing the session indoors or – if working one-to-one, having an open dialogue with the athlete so that they can let the practitioner know when they are becoming overwhelmed. This option only works if the individual is mature enough to understand their emotions and verbalise them. Sporting environments can be overwhelming,27 so it is important to consider all the variables that may impact this.

Kinesthetic awareness is often reduced in autistic individuals: providing proprioceptive feedback to the athlete can supply valuable information to help the athlete move their body using the right muscles. A common example is having a coach apply pressure to the latissimus dorsi when performing a rowing action or spinal erectors when performing a back extension. Reduced kinesthetic awareness often makes performing in variable conditions challenging as it may not be natural to an autistic person to change their direction mechanics on a wet pitch in comparison to a dry one.

When following a new exercise programme, it is important to provide extra time to process the information given and to allow more opportunities for practice and repetition. Waiting for a degree of movement proficiency to be attained should be a guide as to when to progress and get into working sets rather than the time taken. This also applies to the coach’s demonstration and teaching methodology, as rather than following the ‘three silent demonstrations’ guideline that S&C coaches are taught, one may need to do these demonstrations repeatedly to remind the autistic athlete of the movement’s characteristics.

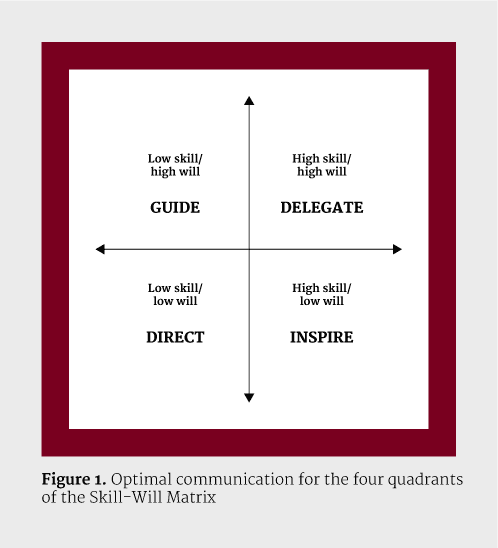

Verbal instruction should be clear, concise, and literal, so as to avoid misinterpretation.11, 46 Non-verbal or visual communication should be well-considered, with precise demonstrations that align with the instructions provided. Visual communication of exercises using pictures and videos can help with the learning process,9 preferably using pictures etc which depict someone with a similar age to the autistic athlete performing the exercises.

Given that autistic people often have DCD or DCD consistent characteristics, verbal explanation of movements is often not enough. Further breakdown of movement components may be necessary to help with mastery and kinaesthetic learning: use verbal, demonstrative and proprioceptive coaching methods where applicable. It is essential to understand that kinaesthetic awareness is often reduced, so autistic people may lack understanding of what actions their body is performing, and therefore trial and error of movement patterns should be encouraged. Autistic people often learn best through doing rather than following a verbal instruction,45 as converting an instruction into movement can be a significant challenge. When the athlete is attempting a new movement and is going through the trial-and-error phase of development, verbal feedback and body language should be positive to help with motivation and engagement.3,47 Timing of positive reinforcement and the use of physical rewards and token prompts have also been shown to help in getting the athlete to achieve new things and increase treatment gains.1

Often autistic people seek reasoning behind statements or given tasks. They need to understand why they need to do something – just saying ‘just do it’ is not enough. When doing sprint drills, throwing a ball up and have the athlete catch it before it bounces twice provides an external stimulus to make the athlete run as fast as they can. Games or challenges like this negate any pushback from the athlete. Combining balls into sprint drills can also provide practice hours and an opportunity to stimulate perception of ball flight and trajectory.

An example of an opportunity to help an autistic individual which may be out of the typical realms of a S&C practitioner is to talk about how they interpret verbal and non-verbal communication. For example, when playing basketball, a player will interpret another's facial expressions and body language to such a degree that they will know how fast or slow to move and to what direction the ball should be passed to them. Talking about this with the autistic participant and pointing out specific cues to watch for will help them develop their understanding and interpretation of facial expression. A common teaching point for this scenario arises when a participant passes the ball when a teammate isn't looking, or too slow on a counterattack, or too fast when trying to maintain possession. This is one example of how social deficits rather than physical deficits can be a barrier in team-based sports. In turn, this provides a unique coaching opportunity: while developing physical capabilities the practitioner can help the athlete to better understand how to interpret other actions, mannerisms, verbal and non-verbal body language and communication tactics used in team sports.

Modifying or adapting exercises is something that all S&C coaches can do; however, when working with autistic people the reasons for modification may change. Normally, one adapts an exercise due to strength, range of movement or experience level, but in the autistic population one needs to consider additional factors including sensory regulation, dislike of change, coordination challenges, motivational strategies, spatial and vestibular challenges, and choice of wording and instruction.

Increased care must be taken when working within the autistic population as they are more likely to lack sporting and S&C experience.26 When introducing new activities, consider their sensory profile when deciding upon exercises. Aiming to meet their sensory needs can help maintain a calm and alert state,38 which helps help prevent ‘meltdowns’ and other challenging behaviour.22

Specific exercise selection follows the generic approach, the only difference is how one may teach and manipulate exercises to provide sufficient motivation and cater for different needs. Exercise selection and programming should follow the same gradual approach to change as previously stated. For autistic athletes, a warm-up or preparatory period should act as an ice breaker,41 which can include finding out their interests, talking about relatable topics etc. The cool-down period consisting of relevant stretches can be used to help improve mobility,35 reflect upon the session,23 praise the participant for their efforts and make them feel a sense of achievement, while also emotionally regulating them for the rest of their day. Standing stretches are recommended to help improve balance, a common weakness in this population.7

Intrinsic motivation can be applied to tweak exercises as autistic people are more likely to engage if the objective of the exercise has personal interest for them. For example, when attempting to do plyometric line hops, an autistic athlete may refuse through lack of motivation or engagement in the session or exercise choice. To combat this and amplify their focus and motivation, a drawing of their favourite character to jump over instead might act as sufficient motivation. Interests should be exploited as a motivational tactic, and although this is a good tool to use with all athletes, it is often not needed. If possible, always select exercises linked to special interests.

Movement impairments or coordination difficulties may hinder participation levels, so it is important to know how to quickly adapt and regress exercises, and how physical rewards and token prompts can help achievement. Explaining how to perform the chosen exercise or movement is important. As autistic people commonly have coordination difficulties, movements like jumping, squatting, or throwing that are natural to most take longer to learn, meaning specific guidance is needed when first attempting such exercises. As autistic people are often as capable as the general population, a coaching attitude based on which exercises to avoid is a negative way to approach S&C. Failure in a safe environment should be encouraged as it provides a learning experience. A prime example is practising bailing a squat or olympic lift: every element of each exercise should be thoroughly gone through and practised before expecting the athlete to lift heavy loads. These movement impairments hamper the speed at which techniques are learnt. High risk exercises like ballistic, plyometric, or heavy strength exercises should be selectively used. It may take much longer than expected to get to a level of competence where it is safe to use these exercises.

When regressing or progressing exercises, the difficulty of the exercise should be evaluated through the idea of how many layers of coordination that movement has. A javelin throw is a good example: a standing throw would involve one layer of coordination – ie, only moving one limb to throw; however, a full run-up would involve multiple levels of coordination, seven to be exact. A layer simply means something else to think about, and although many of these things are natural, for people with coordination challenges they will not be. At the end of the run-up and initiation of the throw, all four limbs are working independently performing a different job; upper and lower body are working separately, the athlete is having be aware of their speed and rhythm to time the release accurately – and all this while having to be spatially aware of the line at the end of the run-up area. This is seven different things the brain has to process, and the body has to do at once, and this is before you start to include intricacies such as grip type, head and foot positioning. Therefore, to regress and progress a movement, simply count the number of components the athlete has to focus on at once. If the athlete is performing a new skill and cannot naturally do three layers, they most likely will have coordination difficulties.

Awareness of vestibular sensitivities are also important as this can impact upon the exercises that they are able to do. For example, forward rolls, ‘stir the pot’ type core exercises or movements where the athlete's centre of mass rapidly changes location – like a snatch – may be challenging and dysregulating. Lack of proprioceptive awareness should also be considered when exercising around others. This applies to group sessions in a hall, pitch or gym where ballistic or plyometric activities may be taking place. It is important to note that the practitioner should not only consider the autistic athlete’s potential lack of awareness and understanding of their own body and objects they may be using to train, but also lack of understanding of others. For example, when working on a track and there are sprinters close by, most athletes recognise that kneeling down implies that a sprint is about to begin. An autistic person may interpret this differently or not at all and not realise what the sprinter is about to do. A strategy to deal with this type of situation is to discuss body positioning and what it implies in relation to movement and emotion.

As spatial awareness is reduced in this population, picking exercises that avoid being in a confined space can be an effective strategy when trying to minimise risks. However, avoiding all team-based activities and small spaces is not a solution to the problem and should be considered only when the participant is over-aroused or dysregulated. To improve their sporting performance, it is important to put them in situations to allow them to learn from their mistakes. Briefing them of the situation and asking them to focus on their body awareness and where they are in relation to others is key to helping with this common aspect of autism.

Due to the range of ability and severity of need among this population, performers require different S&C strategies. Exercise selection becomes less specific, while more focus is placed on maintaining engagement and interest to sustain participation.5 Exercise adherence, consistency and engagement should be prioritised over ‘optimal exercise selection’, as the most optimal training method is one the athlete can stick to. When working with autistic athletes, a standard S&C session could run with little to no changes; conversely, for an athlete with more significant needs the coach may need to significantly adapt the session plan and utilise methods such as distraction tactics to elicit the desired adaptation. An example of this could be: ‘bounce like a kangaroo’, rather than ‘perform three sets of ten pogo hops’. When working on decelerating mechanics, instead of stopping between cones, a game such as ‘the floor is lava’ may be adopted. Working on landing mechanics, a recommended metaphor is to ‘land like they are riding a motorbike’ rather than the ‘ready position’ or ‘athletic position’.5 For the more mature population, gym-based adaptation strategies mainly comprise of avoiding sensory overload. Strategies such as using rubber plates instead of steel ones, reducing music noise, picking less busy times and being mindful of the tactile challenges that a gym environment might present are easy to apply strategies.

Barriers to typical S&C training methods in the gym, track or pitch for autistic people can easily be removed with the right coaching knowledge and expertise. The first consideration for the S&C practitioner is to be mindful that all autistic athletes are individual, but with greater variances than individuals in the general athletic population.5,14 S&C support for autistic individuals and groups of autistic athletes changes depending on numerous factors, including the severity of the condition, level of support required, age of the participant, number of people involved, the sport being coached, the use of motivational stimuli, and most importantly the level of performance the person is attempting to reach. Having a good understanding of the individual’s sensory profile is therefore vital and is why an initial consultation is key.

Coach education can improve using effective prompts and reinforcement of delivery.14 However, clear strategies for teaching coaches how to collaborate with autistic people have not been established.44 Autism research typically revolves around classroom-based education rather than sport or physical activity education.31 Lack of participation and fewer autistic athletes performing at an elite level may only be partially due to the condition itself; much may be down to the lack of coaches and practitioners that are confident, willing, or able to adapt to their individual specific learning requirements – for example, using sensitive, regulatory tactics to prevent over-arousal and therefore supporting sustained session participation. Knowing when to push and when to support an autistic athlete is very individual and something that only experience with that athlete can teach, but signs of overstimulated behaviour can be learnt and are a good indicator of when to stop or move on.

Finally, as displayed throughout this review, frequent examples have been presented of how conditions, exercises etc may affect autistic people and how they participate in sport or exercise. When working within this community, it is paramount that one understands that there can always be a way around a challenge that arises. Whether the situation takes the form of arousal level changes, coordination challenges, difficulty reading social cues or other factors, there will be a way to adapt to fit the needs of the individual. Autistic people have always been expected to fit into a neurotypical world. We recommend that, if you have the privilege of coaching the autistic population, you should try to break the mould and make an effort to see the world from their perspective, for a change.

1. Arkoosh, MK, Derby, KM, Wacker, DP, Berg, W, McLaughlin, TF, & Barretto, A. A descriptive evaluation of long-term treatment integrity. Behavior modification, 31(6), 880-895. 2007.

2. Allely, CS. Pain sensitivity and observer perception of pain in individuals with autistic spectrum disorder. The Scientific World Journal. 2013.

3. Barbera, ML. The verbal behavior approach: How to teach children with autism and related disorders. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2007.

4. Baron-Cohen, S, & Wheelwright, S. ‘Obsessions’ in children with autism or Asperger syndrome: Content analysis in terms of core domains of cognition. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175(5), 484–490. 1999.

5. Coffey, C, Carey, M, Kinsella, S, Byrne, PJ, Sheehan, D, & Lloyd, RS. Exercise programming for children with autism spectrum disorder: recommendations for strength and conditioning specialists. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 43(2), 64-74. 2021.

6. Cordina, C. (2020). Face blindness. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/52399

7. Faigenbaum, AD, Lloyd, RS, & Oliver, JL. Essentials of youth fitness. Human Kinetics Publishers. 2019.

8. Failla, MD, Gerdes, MB, Williams, ZJ, Moore, DJ, & Cascio, CJ. Increased pain sensitivity and pain-related anxiety in individuals with autism. Pain reports, 5(6), e861. 2020.

9. Fittipaldi-Wert, J., & Mowling, CM. Using visual supports for students with autism in physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 80(2), 39-43. 2009.

10. Fournier, KA, Hass, CJ, Naik, SK, Lodha, N, & Cauraugh, JH. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 40(10), 1227–1240. 2010.

11. Groft-Jones M & Block, ME. Strategies for teaching children with autism in physical education. Teaching Elementary Physical Education, 17(6), 25-28. 200

12. Healy, S, Msetfi, R, & Gallagher, S. ‘Happy and a bit nervous’: The experiences of children with autism in physical education. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(3), 222-228. 2013.

13. Johnson-Ecker, CL, & Parham, LD. The evaluation of sensory processing: A validity study using contrasting groups. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54(5), 494-503. 2000.

14. Jones, P, Derby, KM, Engler, JR, & Trotter, T. Training of Novice Trainers to Work with Athletes with Autism Spectrum Disorders in an Ice Hockey Practice Setting. Insights into Learning Disabilities, 16(2), 123-137. 2019.

15. Karvonen, J. Importance of warm-up and cool down on exercise performance. In Medicine in sports training and coaching (Vol. 35, pp. 189-214). Karger Publishers. 1992.

16. Kauchali, S., Marcín, C., Montiel-Nava, C., Patel, V., Paula, C. S., Wang, C., Yasamy, M. T., & Fombonne, E. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism research: official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 5(3), 160–179. 2012.

17. Kersh, J, Siperstein, GN, & Center, SOGC. The positive contributions of Special Olympics to the family. Special Olympics. 2012.

18. Khoo, S, & Engelhorn, R. Volunteer motivations at a national Special Olympics event. Adapted physical activity quarterly, 28(1), 27-39. 2011.

19. Hample, K, Mahler, K, & Amspacher, A. An Interoception-Based Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 13(4), 339-352. 2020.

20. Laumonnier, F, Nguyen, LS, Jolly, L, Raynaud, M, Gecz, J, Patel, VB et al. UPF3B gene and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in autism spectrum disorders. Comprehensive Guide to Autism, 1663-1678. 2014.

21. Lefebvre, C, & Reid, G. Prediction in Ball Catching by Children With and Without a Development Coordination Disorder. Adapted physical activity quarterly, 15(4). 1998.

22. Lipsky, D. From anxiety to meltdown: How individuals on the autism spectrum deal with anxiety, experience meltdowns, manifest tantrums, and how you can intervene effectively. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2011.

23. Lloyd, RS, & Oliver, JL. Strength and conditioning for young athletes: science and application. Routledge. 2019.

24. Malliou, P, Rokka, S, Beneka, A, Mavridis, G, & Godolias, G. Reducing risk of injury due to warm up and cool down in dance aerobic instructors. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, 20(1), 29-35. 2007.

25. Marco, EJ, Hinkley, LB, Hill, SS, & Nagarajan, SS. Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatric research, 69(8), 48-54. 2011.

26. McCoy, SM, Jakicic, JM, & Gibbs, BB. Comparison of Obesity, Physical Activity, and Sedentary Behaviors Between Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorders and Without. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 46(7), 2317–2326. 2016.

27. Menear, KS, & Smith, S. Physical education for students with autism: Teaching tips and strategies. Teaching Exceptional Children, 40(5), 32-37. 2008.

28. Ming, X, Brimacombe, M, & Wagner, GC. Prevalence of motor impairment in autism spectrum disorders. Brain & development, 29(9), 565–570. 2007.

29. Obrusnikova, I, & Cavalier, AR. Perceived barriers and facilitators of participation in after-school physical activity by children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23(3), 195-211. 2011.

30. Oriel, KN, George, CL, Peckus, R, & Semon, A. The effects of aerobic exercise on academic engagement in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 23(2), 187-193. 2011.

31. Orsmond, GI, Krauss, MW, & Seltzer, MM. Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 34(3), 245-256. 2004.

32. Pan CY. Motor proficiency and physical fitness in adolescent males with and without autism spectrum disorders. Autism: the international journal of research and practice, 18(2), 156–165. 2014.

33. Reinders, N. J., Branco, A., Wright, K., Fletcher, P. C., & Bryden, PJ. Scoping review: Physical activity and social functioning in young people with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 120. 2019.

34. Pieslinger, J, Wiskerke, J, & Igelström, K. Stratifying the broad autistic phenotype: Contributions of social anhedonia, mentalizing and face blindness to social autistic traits. 2022. https://osf.io/swm65.

35. Rimmer, JH, Rowland, JL, & Yamaki, K. Obesity and secondary conditions in adolescents with disabilities: addressing the needs of an underserved population. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(3), 224-229. 2007.

36. Rimmer, JH, Yamaki, K, Lowry, BM, Wang, E, & Vogel, LC. Obesity and obesity-related secondary conditions in adolescents with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Journal of intellectual disability research: JIDR, 54(9), 787–794. 2010.

37. Rutkowski, EM, & Brimer, D. Physical education issues for students with autism: school nurse challenges. The Journal of school nursing: 30(4), 256–261. 2014.

38. Sahoo, S. K., & Senapati, A. Effect of sensory diet through outdoor play on functional behaviour in children with ADHD. Indian Journal of Occupational Therapy 46(2). 2014.

39. Serdarevic, F, Ghassabian, A, van Batenburg‐Eddes, T, White, T, Blanken, LM, Jaddoe, VW, Verhust, FC, & Tiemeier, H. Infant muscle tone and childhood autistic traits: A longitudinal study in the general population. Autism Research, 10(5), 757-768. Autism Research - Wiley Online Library. 2017.

40. Stanish, HI, Curtin, C, Must, A, Phillips, S, Maslin, M, & Bandini, LG. Physical Activity Levels, Frequency, and Type Among Adolescents with and Without Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47(3), 785–794. 2017.

41. Stephenson, J, & Carter, M. The use of weighted vests with children with autism spectrum disorders and other disabilities. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 39(1), 105-114. 2009.

42. Sumner, E, Leonard, HC, & Hill, EL. Overlapping phenotypes in autism spectrum disorder and developmental coordination disorder: A cross-syndrome comparison of motor and social skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(8), 2609-2620. 2016.

43. Tyler, CV, Schramm, SC, Karafa, M, Tang, AS, & Jain, AK. Chronic disease risks in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: forewarned is forearmed. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities, 116(5), 371-380. 2011.

44. Watkins, L, O’Reilly, M, Kuhn, M, Gevarter, C, Lancioni, GE, Sigafoos, J, & Lang, R. A review of peer-mediated social interaction interventions for students with autism in inclusive settings. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 45(4), 1070-1083. 2015.

45. White, R. Helping Children to Improve Their Gross Motor Skills: The Stepping Stones Curriculum. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2017.

46. Whyte, EM, & Nelson, KE. Trajectories of pragmatic and nonliteral language development in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of communication disorders, 54, 2-14. 2015.

47. Yanardag, M, Yilmaz, I, & Aras, Ö. Approaches to the Teaching Exercise and Sports for the Children with Autism. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 2(3). 2010.

48. Zantinge, G, van Rijn, S, Stockmann, L, & Swaab, H. Physiological arousal and emotion regulation strategies in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(9), 2648-2657. 2017.

Isaac Hay BSc, is the director of Hays Coaching, which specialises in strength and conditioning and coordination development coaching, and has extensive experience working with neurodivergent clientele. Over the past five years Isaac has used his unique and intuitive knowledge to bridge the gap between occupational therapy and strength and conditioning. Isaac provides 1-1 and group sessions for all ages as well as staff and coach training on neurodiversity.

Prior to working at the University of Essex, Edge Hill University, University of Cumbria, and St Mary’s University, Louis worked as a S&C Coach supporting national and international athletes as part of the university’s student-athlete scholarship and performance sport programmes. Between this role and his private practice, Louis helped prepare athletes for numerous elite competitions including the British Athletics Championships, European Athletics Championships, Pan American Games, Commonwealth Games, and Olympic Games. Louis has published extensively with over 30 peer-reviewed journal articles, two book chapters and his Ph.D.

Rik holds BSc (Hons) degrees in sport science and sport rehabilitation and an MSc in applied biomechanics as well as a PGCHE in academic practice. He has 15 years+ experience in private practice in the field of injury screening, profiling, and rehabilitation and conditioning with private clients, mainly within endurance sports and support team experience with British Triathlon, travelling to two World Championships.